Black Folk Just Being: Karim Brown on the Everyday

by THE EDITORS

July 18, 2025

The featured artist for our Fall 2022 issue, Oblation, Philadelphia-based Karim Brown characterizes his photographic art as an act of making rather than capturing. In this interview, he sat down with AGT associate editor Anyabwile Love, to discuss Brown’s relationship to Black Studies practices and what it means to see the people of Black Philadelphia.

AGT: It’s 8PM on a Sunday, tell us the life of a teacher and artist. A father of four young children, three of which live with you and your partner. What is that life like?

KB: It’s hard. It's challenging. It often-times leaves me feeling discouraged. The pressures of showing up as a husband and father overtakes my desire to even practice my art. So when I am not able to hit the streets and photograph moments I find myself reading more. Which in turn improves my ability to teach better. So in a certain kind of way when I am unable to photograph I lean into my craft of teaching as an art for me. And figuring out how to better myself in the classroom.

AGT: How do you steal away time for yourself as an artist? Not just in the practice but in the time and thought that it takes to just be in your head with the work?

KB: I sit in my garage. I sit outside and look at a photo book. As I'm sitting with the book, I am listening to [John] Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Charles Mingus, and I love Max Roach (we share the same birthday!) As I am looking at the photos and listening to the musicians I'm thinking of the moments so that when they do arise I am ready. I’ve also been writing more…free writing. Or I might try to write a poem. It’s my way of trying to adhere to the art. My art, the artist.

AGT: Thinking about time a little more. What are the things that keep you up? Specifically around your photography? Are there ideas that are germinating or moving with you, circulating in your mind that you haven’t finalized but are working through?

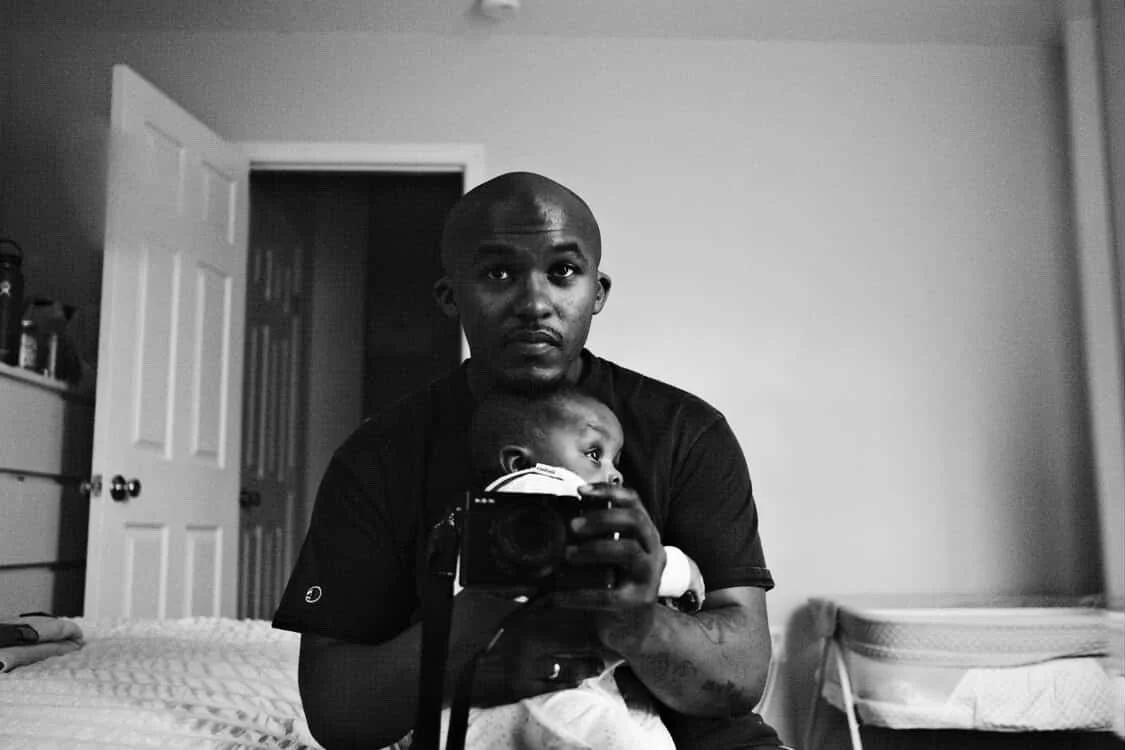

KB: Yes. I am really interested in this beingness, just existing. Like I often imagine myself [Karim’s toddler daughter walks in the room and asks to be covered up in bed]. I’m often reflecting on moments just like that…of walking by with my camera and photographing a Dad engaging with his daughter. Like stolen moments like that. What are Black folk doing when we are just sitting still…just being. Those are ideas that weigh heavy on my mind. And how I can be better prepared to document them. Also because I can’t hit the streets as much I’ve been appreciating more of what's in front of me. [Karim exits to tuck his daughter in] So because I can’t hit the streets I'm just photographing the kids running in the house. Or them jumping off the bouncy house in the backyard. Or Britt (his partner) kissing them. Or if at the school, just documenting the students doing their thing. So those are the moments that are most accessible to me now. I read somewhere that photographers get overwhelmed with trying to find the moment when they are right in the moment and never being able to appreciate that from right where they are.

Karim Brown, from On Being a Child, 2022

AGT: I know it’s building into something else but can you talk about your We Black series. What does that title mean to you? How did you develop that?

KB: I read this essay by Steve Biko called “We Blacks” in his I Write What I Like. That whole essay was just fire to me. That’s where a great portion of that project came from. And me reading Steve Biko’s work was like a love letter to Black folk. I understood him. Him laying out, “this is who we are, this is who we were…and it just is.” So I thought of how do I photograph in the vein of Biko. I just love Black folk just being. It’s just something really beautiful about it. I don't know how to explain it. Christina Sharpe in Ordinary Notes spoke about removing herself from the spectacularity of things and really focusing on the mundane. The everyday.

AGT: You’ve spoken a bunch about the terms shooting or taking pictures of Black folk. You’ve used the terms making a photograph, bearing witness, recording a moment instead. But once you step into this space of Black folk just being with a camera something happens when even folk realize that they are being photographed. Have you considered what happens when you enter into those spaces?

KB: The moments that folks are able to see comes from a much longer time of me just walking around [the neighborhood]. And being in these spaces. The camera may be on my neck but I’m not using it when folk are first engaging with me. Sometimes six months to a year—I’ve thought about how folk are getting used to me… “Karim with the camera and not Karim is coming with the camera.” Early on in my practice I read that, “you have to put your feet in the soil.” We can't deny the fact that even as insiders there is always a questioning of our my genuineness. How genuine am I? Am I extracting something? So it often involves walking the neighborhoods and building relationships. So I may miss a moment. But it allows for greater moments later.

AGT: You mentioned Sharpe, Biko and a couple other folk earlier. We can’t talk about who you are as a photographer without including your Black Studies background. How do you anticipate your studies as a Black Studies student will continue to inform your practice and the stories you want to tell and imagine for us?

KB: Majoring in Black Studies is a double edged sword. ‘Cuz it’s like, damn I know…but also like, damn I know. Because of Black Studies I am hyper aware of how I show up in spaces. I understand because of my studies that Black folk have this relationship with the West where people are taking things from them. And I am always aware of that. I always think that I don't want Black folk to feel that I am taking something away. Black Studies is a moral compass for me as I am navigating the streets or whatever space I am in. That I am not spectating or gazing [at] Black folk. Black Studies has taught me to think about how I look with or alongside Black folk and not at them.

AGT: In 2023, you had a solo exhibit [Beloved] at the African American Museum of Philadelphia. For a young artist that is huge. I know you tend to keep things in perspective. Internally, I'm sure it's something that fills you with joy. Maybe even anxiety or a fear of what's next. During the time of your artist talk which was toward the end of the exhibit, did it help you to begin to stretch out your ideas more? To think beyond that space in relation to your work? Did having that help you to think longer down the road about your work?

KB: If I am being honest I didn't see it. That exhibition was a very weird moment for me. I was filled with gratitude that I was in that space. But I needed folk to remind me that this was a big thing. Because often I downplay my achievements. Which is something that I am actively working on. I don't know if I was looking for it or if I ever felt validated. At that moment I didn’t feel validated. If anything it was a goodbye letter to my first wife. It was a sorrow song. You know, I was pulled into that space literally two months coming off of the death of my first wife. She in many ways was the one who pushed me to pick up the camera. I remember she gave me $500…$1000 to try to keep my camera that produced many of the images that showed up in that exhibit. It was like the album that everyone waits for from their favorite artist that they know is gonna be fire ‘cuz they were down in the dumps. That's what it was, folks were happy for me. I was happy to an extent. Because a lot of those images were made in the first home that I shared with her. Where I brought two humans into the world…with someone who is no longer here. If anything it was a goodbye letter. I couldn’t see the validation. I had validating moments throughout the exhibit. But if I truly felt validated at the time I wasn’t able to see it for myself.

AGT: Let’s talk about the soon to be released photo-essay book, My City Need Something. I know that this is part of the goals you have for yourself. Can you talk about the project that you are doing with Christopher Rogers?

KB: A year after our initial convo Chris hit me up and was like, “are you willing to meet with the publishers?”

AGT: What was that series of events for you?

KB: The first thing I did was hit you (Anyabwile) up. You know. I was like “is this real, should I follow through with this?” I’ve been thinking of Hughes and DeCarava’s book and was like, “damn we about to do a project like that!” So I was excited. But then that negative talk was in the back of my head. Like, “nigga you aint done your own thing yet. Where’s your monograph?” So I am always combating things that feel real in the moment. I was excited and discouraged all at the same time. Shout out to therapy. ‘Cuz I can finally acknowledge that I was feeling both at the same time. I was really skeptical. I had no immediate relationship with my co-author. I had to be vulnerable, fragile if you will, in being willing to go into this relationship with this guy.

The project is a response to the artist PNB Rock’s lyrics, “...my city need something but I don't know what it is.” Me and Chris Rogers are attempting to respond to what we think the city needs. And so it involves Rogers writing essays to accompany each photograph. The beautiful thing and what I truly appreciated was that the photographs were not preselected. Rogers reached out and said for me to send him images I wanted to use and that he would write to them as opposed to him selecting them ahead of time.

Karim Brown, from On Being a Child, 2022

AGT: What was your selection process like?

KB: I selected like 10-20 images. I think twelve ended up in the book. I would look at a photograph sometimes for an hour straight. And would try to anchor the idea of beinghood or beingness. I would look for whether the images show this or is it too posed? And if it’s posed then how much am I taking away from the idea of Black folk being. I realized any show that I have been in I’ve selected photos that are almost autobiographical. How do I tell my stories through images of other folk?

AGT: Are you listening to anything or anybody? Are you reading anything unrelated to your work? The shit that just fuels us? Are you doing anything that is filling you now?

KB: Henry Dumas. I’ve been reading his compilation of short stories. Them shits take me somewhere else. I never really liked fiction. It was a combination of reading Dumas and taking a Black literature class. I just love his shit. I remember talking to Rogers and wondering how I can make photographs that parallel the world that he creates? That would be a crazy project if I can ever do something like that! The way Dumas has me wondering I want folk to wonder about my photographs. I want folk to wonder what was going on in my mind. I want them to leave and ask, “Why does he love Black people so much? Where does his love for Black folk come from?” Also I've been listening to Immanuel Wilkins’ “Fugitive Ritual, Selah.” Oh my god, I play that song constantly. I hear the Baptist church I grew up in. I hear it all. I hear Black folk in it.

Karim Brown is a documentary photographer living and working in North Philadelphia.

Keeping the Black Philadelphia community and its people at the forefront of his mind, Karim uses photography to intimately engage with Black ways of knowing and doing that he has been immersed in his entire life.

Using Black Studies as the foundation of his work, Karim’s photography considers how Black folk understand and tell their own stories through the Black gaze.