Blues As the Light Passing Through Shadows of Sorrow: On Remica Bingham-Risher’s Room Swept Home

by JULIA MALLORY

in Fall 2025

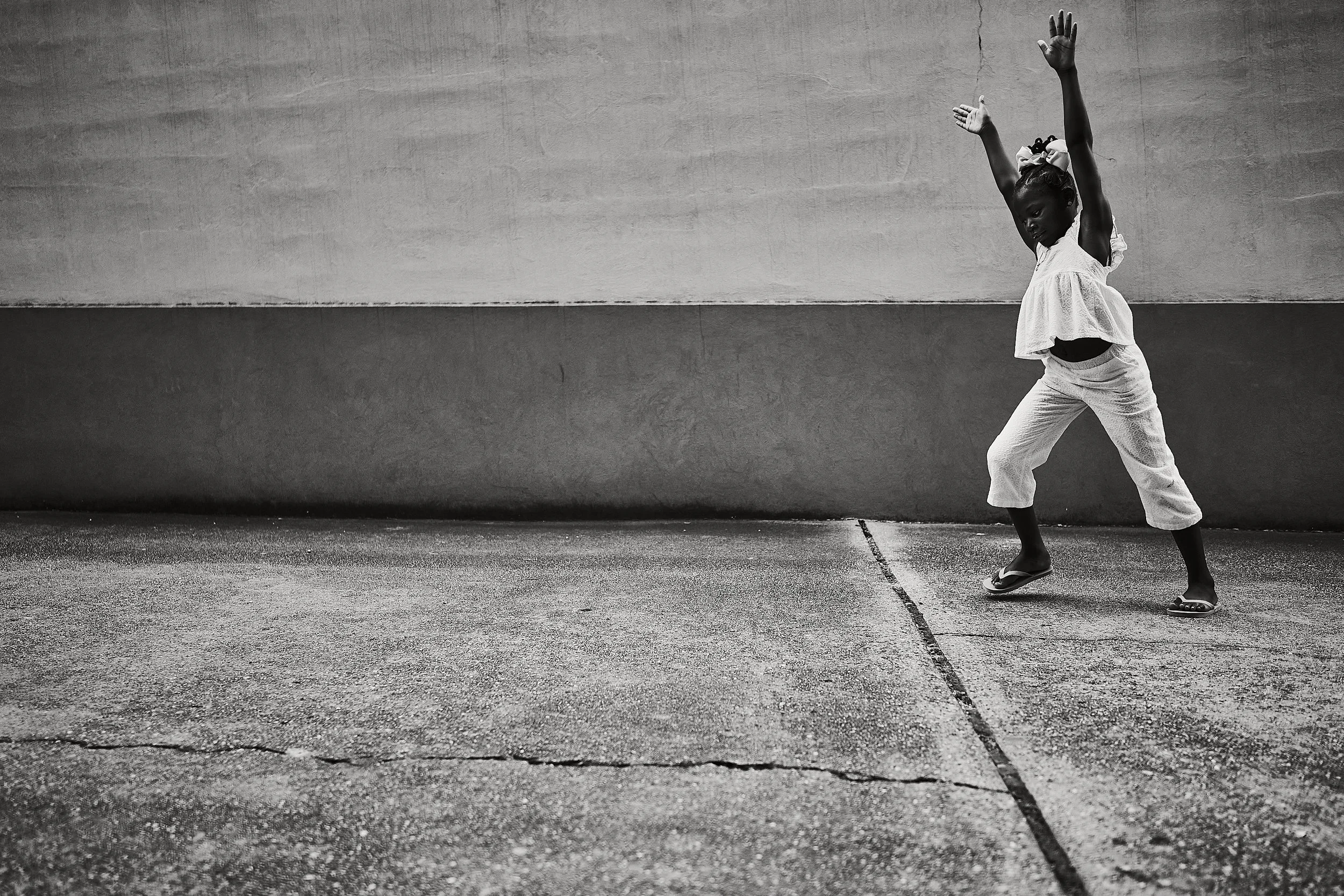

Tafari Melisizwe, “The Teacher - Jackson, MS,” 2025

In September 2024, I fell into the rise and fall of Remica Bingham-Risher's words in a packed ballroom at Furious Flower IV: Celebrating the Worlds of Black Poetry, a conference that only convenes every ten years. An only-every-decade gathering brings its own magic. It settles you into what cannot be cheaply extracted, only savored. And perhaps my feeling in the moment was heightened by just how rare the occasion was. Poets off the shelf and at the podium. Or next to you. Legends assembled and in the making. From the same stage, Nikky Finney held us in her hands with an elegy, “On the Good Ship Elijah McClain,” which took her four years to write.

I was aware that Bingham-Risher's latest collection was out in the world and I wanted it. But I convinced myself I needed to first work my way through my TBR pile. As a collector, I employ all sorts of reasoning to justify my book-buying habits. On this night, the sign would come by way of a single line from the poem, “There Is Nothing In Your Story That Says You Should Be Here,” which read: “You are a spectacular disruption” (114). I stood still in a room full of movement because what does it mean to understand yourself as no ordinary miracle? It is one thing to know your people's prayers are still moving through the cruelty of the world, but it's another to share this understanding in a moment of witness. This single line fed a hunger in me that I could not name but didn't need to. Bingham-Risher said all that needed to be said, touching what needed to be felt. In a matter of moments, I was in the long walkway outside of the ballroom feeding my funds to the bookseller to acquire a copy of Room Swept Home. From the stage Bingham-Risher issued the call. This is my response.

In the opening to Room Swept Home, Bingham-Risher states that “the poet's job is to make the dead become the living” (xx). A possible feat when we speak their names and share their stories. Growing up, I couldn't say that someone, especially an adult, had told a lie. I could only say that they were “telling stories.” So either those same stories are affirmed and grow in the best ways to become family folklore, or they are admonished never to be revived, until a new generation comes sniffing around these tales until they offer a revelation. In Room Swept Home, Bingham-Risher is her family's folklorist, her nose wide open for the truths that have shaped her lineage.

The collection is wrapped in blues and brightness, its cover art featuring elements of collage, reminiscent of the layers of history it contains. It is divided into five sections, two of which are titled after matriarchs in her family, her “paternal great-great-great-grandmother Minnie Lee Fowlkes” and her "maternal grandmother, Mary Etta Knight” (xix). It also includes a notes section that traces her literary lineage. The opening epigraph is from Fowlkes, “I just know I could if I knowed how to write, and had a little learning/I could put off a book on this here situation.” Ms. Folkes may not have written down the words within Room Swept Home, but she absolutely managed to collaborate on this body of work across space and time, her learning in the life she lived.

With a pen anointed with ancestral remembrance, Bingham-Risher moves words and worlds, a skilled poet, tacit in her technique. And with her gift, she revives a generation and breathes life into their experiences. An energetic intervention of sorts, that manages to touch the deep parts within us, so we may remember our own dead. The work wonders, do you know their names? And if you know their names, do you know their stories? Perhaps the reader called out in the poem “because the scale of our breathing is planetary, at the very least”: “You know nothing of/the depth of my grief, and the leagues of my love” (86). Room Swept Home should make us all want to try.

At the heart of the collection is a saga of Black folks who learned how to “make family anyway we can” (25) Their stories detail layers of loss and longing, but also love:

anywhere they landed

better than the toil

they'd left behind but everybody

missed something, someone,

dance for joy, danced for love,

home a dwindling second line (46)

Through Bingham-Risher’s ancestors, we meet Black women as waymakers in the worst of times, again the grammar of survival, who “Make do however we can” (31). A legacy that persists, that shifts: “Throwing rent parties, taking in laundry,/in the kitchen making plates or styling hair.” (31) And Black women as healers:

...they

laid their hands on me

[…]

brought willow bark and ginger, said a soft prayer.

Tied the healing string in knots until the moaning stopped.

Then took a comb to my hair. (34)

We meet people that understand caregiving as a communal practice. A people once dispossessed would speak it plain, we all we got: “we the communion” (31) and “we our own assembly” (34).

Emerging from slavery, we follow their perpetual pursuit of freedom, including fighting for it abroad and the red summer of 1919 when white supremacy sought to shut down

“colored men believing/they are worthy of honor” in a land where “every summer is red” (30). This legacy, also included outlawing literacy for Black people and later would force some out of school and back into the fields:

At twelve, she left school,

worked in the tilled rows of

field like most” (45)

which would later require an alternative means of schooling as we learn in the ghazal, “Night Class, Peabody High School”: “Most of the class twice or three times as old as the teachers here./What will they make of crooked teeth and letters?” (33).

We also learn of Mary’s hospitalization at the Central Lunatic Asylum. Along with a photograph of the ledger from 1941 where she is signed in, Bingham-Risher reimagines the medical record as a poem, delivering a line that haunts: “I do not think I have all that belongs to me” (52). The cruelty of the institution made clear and further detailed in Mary's voice in “To Calm the Mind”: “water sprayed hard […]/until we pass out or shut our mouths” (54).

The images that accompany the poems tell of their own tales while complimenting Bingham-Risher’s words. There are tobacco workers of all ages in 1899, steadfast in their labor where sections of the image contain over exposure, producing a glaring glow. One photograph is the source material for the ekphrastic “Child with Playthings in Black and White”, a nod to the invisible labor of a Black woman holding it all together beyond the frame: “On the outskirts of the room, binding a sheet:/brown hands and breasts rise against a well-made crease” (62).

Through the collection, we contend with motherhood as a portal: “Why are mothers every doorway, every host” (58). Women who issue wisdom and warnings, including insight on the generational hand-me-down of masking emotion: “Fix your face/I tell my children/something that's been told to me” (60).

The second to last section of the book, “The Lose Your Mother Suite,” a gathering of a crown of sonnets, closes with a nod to Saidiya Hartman, whose work it borrows its title from. Each ending a beginning. A return to the source, employing the West African concept of Sankofa, to go back and get it. Bingham-Risher wants us to remember. But we should also understand that this remembering is not to be idealized as she informs readers in an interview with Tamara J. Madison of BREAKDOWN: The Poet & The Poems:

That is difficult work. It's heavy work [...] I just felt like they would not let me go. They woke me up at night [...] I saw them in the mirror. I heard them [...] And always it was like ‘you're not doing enough. You haven't done it yet.’ [...] And for a long time I just felt like, y'all are wearing me out. [...] it's not all easy when you're doing family work. When you're doing historical work.

Further acknowledgement of this reality is embedded in the poem “VII. I was born in another country”: “The mangled cord/of history wears us all out” (98). Can this cord be righted? Can we heal?: “God,/when are the women allowed to grieve?” (103).

And in the same vein, in “Refusing Rilke's You must change your life”, we meet a memory keeper:

“6,000 books and counting [...]

Old concert leaflets, [...]

above/the dresser filled to the brim with us.” (118)

Black women who skirt the edge of hoarding and collecting, or building their archive, as the artist, archivist, and curator Sierra King encourages. Room Swept Home reminds us that the archive is not without complication. Furthermore, it manages to capture a range of Black life and interiority while leaving us with the understanding that even in the darkest hours, “their suffering wasn't everything” (120).

Poems (in order of appearance)

114: There Is Nothing In Your Story That Says You Should Be Here

xx: In the Corridor

xix: In the Corridor

86: because the scale of our breathing is planetary, at the very least

25: Ruddy

46: Mary perfects the Charleston, recalling it for the next eighty years

31: the Great Depression was hard to distinguish when poverty was always a way of life

31: the Great Depression was hard to distinguish when poverty was always a way of life

34: The Tenderness of One Woman for Another

31: the Great Depression was hard to distinguish when poverty was always a way of life

34: The Tenderness of One Woman for Another

45: Mary perfects the Charleston, recalling it for the next eighty years

33: Night Class, Peabody High School

52: MASTER INDEX: CASE RECORD

54: To Calm the Mind

62: Child with Playthings in Black and White

58: Two Months and Thirteen Days

60: Clean white homes and smiling black servants appropriately attired in language and dress

98: VII. I was born in another country

103: Diaspora was really just a euphemism for stranger

118: Refusing Rilke’s You must change your life

120: I am trying to carve out a world where people are not the sum total of their disaster

Julia Mallory is a poet, collage artist, and filmmaker. Her reviews have appeared in Emergent Literary, 68 to 05, Sugarcane Magazine, and elsewhere. She is a poetry editor for The Loveliest Review and founder of the creative containers, Black Mermaids and TEN OH! SIX, a multigenerational gathering space for collective learning, creativity, and connection.