“multiplicity and an awareness of something missing”: baaba and the art of fragmentation

by THE EDITORS

February 7, 2026

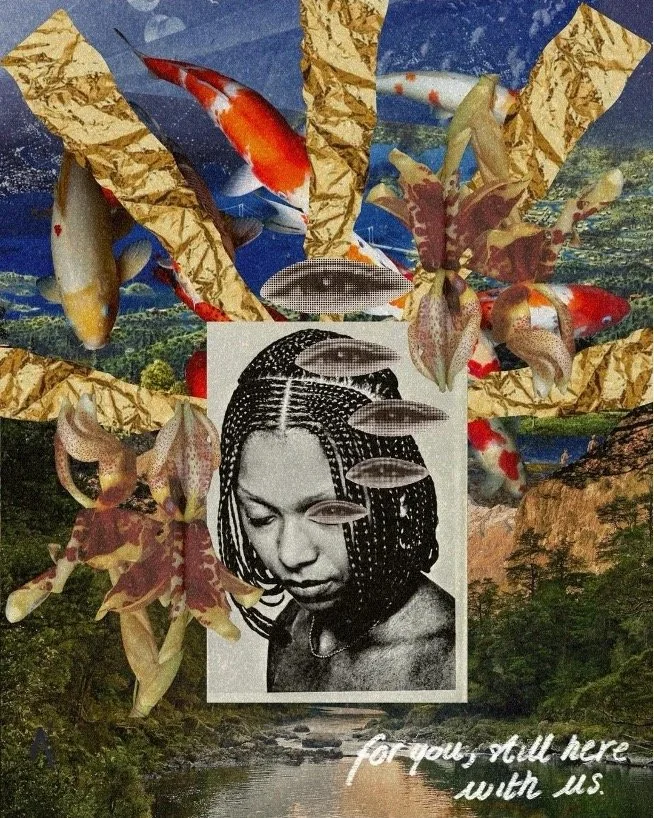

baaba, inner gardens / a self portrait, 2025

UK-based artist baaba was our featured artist for our Spring 2023 issue, Flight. Her work considers the fragmentary record of the archive as a form of collage and for re-staging our expectations of documentation and preservation. She recently sat down with AGT editor Josh Myers to discuss her practice.

AGT: What was your introduction to collage as a practice and what pushed you to engage this as an artist? What advantages and disadvantages do you see with this medium compared to others?

B: I was introduced to collage as a medium through an old friend, a suggestion that came in a time of frustration with the visual mediums I was using at the time. I began in July 2022, during a vacation in Ghana: that first step was a playful experimentation with the medium itself. My very first works do not feature people at all. I appreciated the versatility, the freedom I felt with the ease that came with worldbuilding and tapping into the surreal. However, the moment I started introducing people within my collages, I gravitated towards adding sound and some form of movement. I wanted to move from static to stillness, which was conveyed through videos used as backgrounds, moving elements, and stop motion. What made my experimentation bloom into a practice was a few DMs I received from an online mutual of mine, who became a person very dear to me. She saw my experimentations with digital collages and sent me the Black Collagists Instagram page and the works of Thato Toeba. That interaction meant a lot for me not only because it was my first time feeling witnessed in the art I was starting to create, but because it taught me the intentionality I needed to materialise that art.

The culmination of me using collage as a modality of expression and language came when I lost my poetry. Written poetry used to be the means by which I would attempt to put together a language and form that could be a site of care and rest for the heavy feelings I carried on my chest, mind, spirit, and skin. I've known poetry to be a force that (re)assured my movement in this world, teaching me to hold my fear and grief with a haunting tenderness and softness. Losing it was strange and quite confusing, but also revealed a void around my sense of identity. I came to collage with a mind struggling to make sense of the fragmentation that I was experiencing at the time. Little did I know, at the time, that this fragmentation had always been there: it held a form that required a confrontation that transcended relying solely on language. I think that is the main (dis)advantage of collage, the dealing with fragments and their limits. There's fragmentation in the ownership of the images accessed, in how they are used out of the context they have been placed in, and in how they become a different being, part of a different story. The process of research for material can be extremely chaotic, especially when the original source is unaccessible. There's multiplicity and an awareness of something missing at the same time, and it can be challenging to find the best way to achieve wholeness. I had to learn to sit with the discomfort of how collaging can be a haunting process, demanding a certain hyperawareness, especially when creating from a place of emotion and Spirit.

AGT: Your collages seem to combine color images with black and white images one might associate with the "archive"? What is your relationship to color and black and white? How does the archive emerge in your work?

Initially, there was no intentionality behind my tendency in using black and white pictures: they were more accessible. However, I eventually noticed how the contrast created between the people and the background accentuated a certain presence, and a demand to notice that presence. This oriented me towards practicing collage as a methodology of memory work and a form of critical fabulation, uncovering visualities of ordinary living through my archival search and exploring what might have been, or what could be. The aim was to spark curiosity and wonder, not towards the images themselves, or the single elements within the composition, but towards the stories, their times, and what they passed on. I took a lot of inspiration from Afrofuturist aesthetic for my earlier collages, with the “moving from what it was to what it is in order to inspire what is yet to come” as the main overarching theme.

As I became more dedicated to Black Studies in my own academic journey, I focused on exploring a possible (re)assemblage of the archive, reflecting behind the ethics in the processes of selection, nomenclature and citation, curation, preservation, and their implications within my works. The main questions I ask myself are: how do I preserve the lineages in a way that is recognisable to those for whom I'm creating, without falling into the violence of spectacles? What is the language I use to name my pieces? How do I describe, and what can I reveal whilst trying to protect the opacity coming through? I started pondering on the implications of exploring blackness within solely black and white imagery. What happens when I insist on representing us through a lens that reproduces the Western understanding of time? What happens when I intentionally direct the eyes to the person at the centre of the composition, knowing that we live in times of hypervisibility and surveillance? I gravitated towards what remained unnamed and unresolved with the archives I explored, and felt the need to convey that into a certain blurriness. Not only did I start using pictures in colour to reduce the contrast and the fragmentation, but I also started playing with image settings, moving between transparency and opacity.

Lastly, the archive concerns my own personal history. I use the term fragmentation a lot because that is how I experience my own memory and identity. There are many gaps, many fractures. Some of my favourite pieces feature younger versions of myself, coming from pictures I don't remember taking. The archive I'm preserving is one that holds the memories captured by those who watched me grow and carry my family's lineage. I am trying to know her story, and tell it according to her. I would describe this through Toni Morrison's words: “The pieces I am, she gather them and give them back to me in all the right order.”

AGT: Another element evident in your work is nature and the environment. Can you comment about the role that space and ecology play in your artistic imagination?

B: The addition of nature constitutes an act of memory: the memory of the lands we walk on, the memory within the lands we walk on.

I love plants, and I love being in the presence of nature. It came almost instinctively for me to replicate my connection to the land within my work. In the first few years of my life, I grew up in a polluted neighborhood. My mum used to tell me of how I'd come back from school showing physical reactions caused by the prolonged exposure to the chemicals in the soil. What was space for play and joy for me, was also a space that was impacting my health. On the other side, I grew up watching my mother tending to her plants, calling her “her children”. We often use terms like “branches”, “roots”, “seeds”, “decay”; our actions are “blooming”, “pruning”, “grafting”, “flowing”. I love the idea of exploring the affect and kinship between us and plants, the nature we are part of. Reflecting around the representation of landscapes in art played a significant role in shaping my integration of nature in my work. Thinking about certain landscape paintings and their ties with colonial history, the colonial gaze they hold in representing the conquerable greatness of nature, that nature within Indigenous lands; the top view, in surveillance, that attempts to capture the vastity of the space and life within it, and the acts of conquest, displacement, exploitation, ecological destruction. And how all of that is encapsulated within the definition of beauty I was taught in school.

Beyond plants, another major element featured in my work is water. I draw directly from the concept of tidalectics (Kamau Brathwaite) and water as a site of memory (Toni Morrison). As the first born daughter of Ghanaians who migrated in Italy, thinking about the politics of water is something that marked my whole life. Whenever I go to Ghana and visit my parents' hometowns, I am aware that I am close to both the sea and the Elmina Castle. I grew up watching flashing images of families trying to reach the shores of Italy, of people dying in the Mediterranean waters. My mum made sure I also learnt how to swim. I understand water as a main part of not only my being, but of blackness as a whole. I don't think I would be able to make art and convey the very concept of memory without water.

baaba, for y(our) loved ones, 2025

AGT: How would you relate the previous questions to the issue or idea of Blackness?

B: It is a continuous stream of thought around the ordinary of Black life, and how it is memorialised. Even when thinking about archives and other institutional sites of memory, I am consistently confronted with the fact that the documentation of Black life wasn't meant to happen to begin with. I spoke of haunting. I tend to worry a lot about the issue of the generativity of making art from a place of blackness, created as a space and condition of abjection. Is it possible to move from and beyond that condition? And there is a certain madness to this, in trying to define a humanity, through art, that rejects that which placed our living in a position and being of abjection. The fragmentation within the acts of representing, feeling, being human. The decay of the attempts/previous versions of conservation and resilience. Resilience is a topic I always mention in my work, because it plays a significant role in maintaining those controlling images dictating how we need to be, how we must function. I guess I am exploring ways to also renaming and being me, on my own terms.

AGT: What's next on the horizon for you as an artist?

B: I'm currently studying black practices of art curation. I am interested in understanding how space is created, and I hope to be able to integrate this within my practice not only as an artist, but also as an educator. Beyond this, I am continuing my PhD project, which is an exploration of how Black women use visual arts for mental health.

baaba is a Ghanaian-Italian educator and transdisciplinary artist based in the UK. Her practice, deeply inspired by critical fabulation, tidalectics, and critical humanism, involves formulating sites of knowledge, memory and healing through collage art. She seeks to conceptualise methodologies of refusal by formulating grammars of seeing, feeling and being that reject spectacles, extraction, and surveillance.

She is currently pursuing a doctoral degree in Education and Psychology, exploring visual art practices of coping used by Black women for their mental health.