by AGT EDITORS

December 22, 2023

In May 2022, associate editor Anyabwile Love discussed the journey and practice of of textile artist and designer Bakari Akinyele, a 2020 graduate of Howard University, Henry Luce Scholarship winner, and Fall 2021 featured artist for A Gathering Together. An artist deeply concerned with sustainability, Akinyele discussed the evolution of his vocation, familial inspirations and influences, and the significance of global travel in his decisions to work with indigo dye.

(Their conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

AGT: Let me start from the end, man. I know with A Gathering Together, of course, we had a lot of photography as well as your paintings, the blue pieces, because that was a feature of what we were doing with AGT. But is there anything coming up the road for yourself that you’re excited about, that kind of gets you up in the morning? Or that frustrates you, even? Because sometimes that “new” can be frustrating. What’s coming for you?

BA: I have a couple of things in the pipeline. My first paper will be published in the Design Museum Everywhere book that’s coming out later this fall. The title of the paper is called “Love Sourcing: Finding Sustainability Through the Intangible.” And essentially in the paper I talked about how love is the most sustainable mystery that we all have access to. And the paper is encouraging designers to source the idea of design around how they can use the thing that they’re designing as an expression of love for another person. So I give the example of how [in] a tea ceremony, the teacups and the tea are equally important within that ceremony. But it’s the ceremony itself and the connection that is established through the ceremony and expression of love to another person that makes us really value the teacup in addition to the tea. Caring about that object and being able to develop an attachment that’s centered around love through the object encourages and increases the likelihood that that object will make it into the future. Because we’ll care for it, we’ll make sure that if it’s chipped, it goes to get fixed. I think that concept applies to anything design-based. I think about the car that I was given and how I have a responsibility. That car came from a loved one. So, now I have to take care of that.

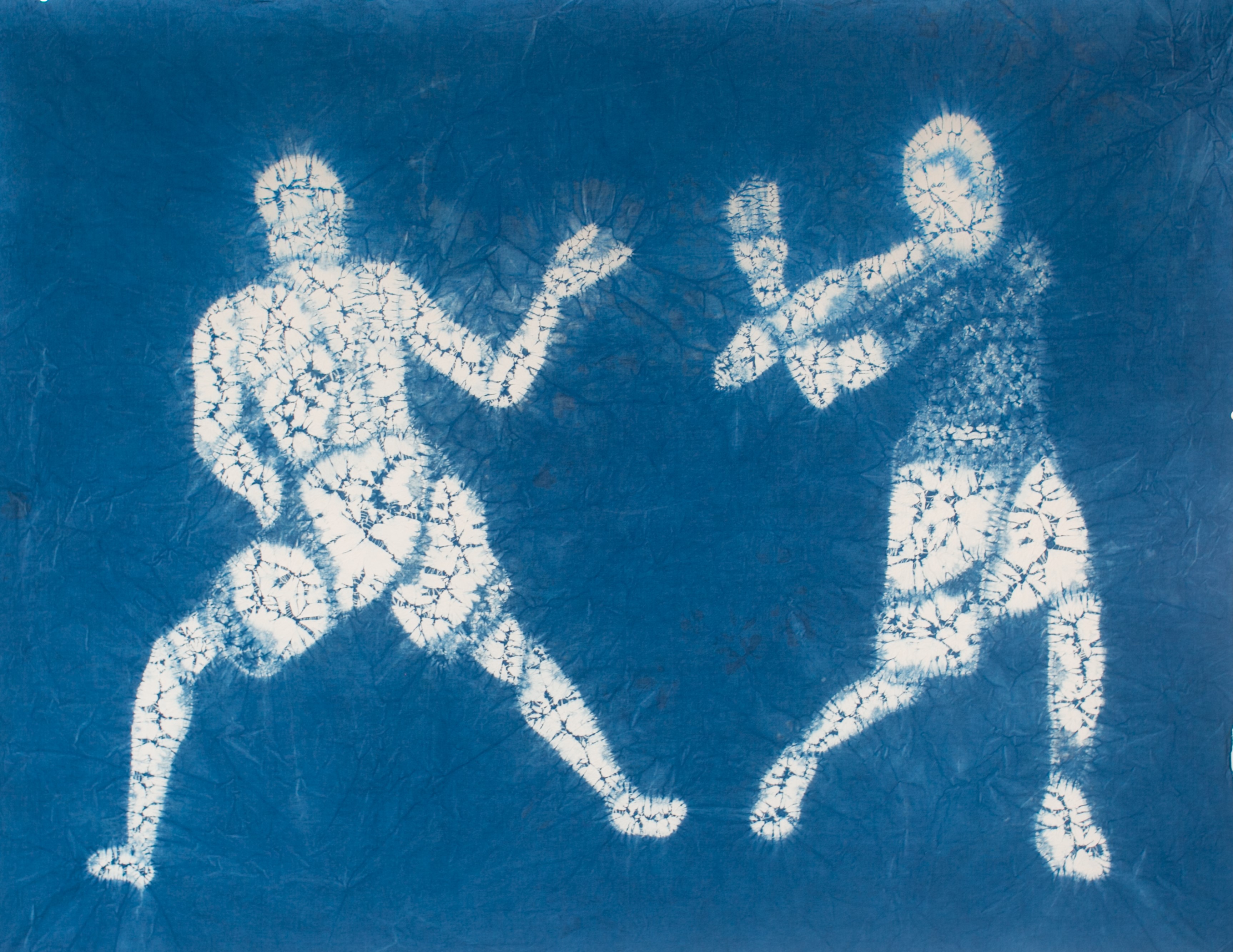

I work seasonally. I don’t work during the winter unless it’s writing. In terms of making visual art, I move by the season. So during the winter, I’m resting because that’s my low-energy season. So I try to conserve my energy. Now that spring has passed, I’ve been working on ideas. And now that it’s summer— high-energy period—it’s time to execute. I’ll be moving into a new body of work— a body of work that’s a continuation from my Movement Series. I feel like it’s a little difficult to talk about it because I don’t wanna lie and not do what I’m saying. But what I will say is that I am continuing down the path of exploring how movement is used as a healing practice. And even thinking about it from like an individual, biological level to a community level. When you hurt your hand, your body’s natural response is to shake. Because that shaking relieves the trauma of that pain. Within the Movement Series, what I’m exploring now is the healing process. Not focusing on the fact that the hammer hit the hand, but the fact that the hand is now shaking and it’s trying to repair itself. Within the community level, healing [begins with] imagining the part of the healing that has to do with projecting ourselves and prophesying about what the future is gonna look like.

The analogy I’m working with is karate or like martial arts, the exercise of chopping through a block of wood. When you’re chopping a block of wood, the instructors tell you not to imagine breaking the wood, they tell you to imagine your hand on the other side. So the act within the aesthetics of my body of work, the act of chopping the wood, is the martial arts. The majority of my work is focused on movement-based expression, which is like the other side. Being able to whoop somebody’s ass but with the purpose of being able to set yourself and your community up for free expression in the future.

And it came from that environmental standpoint of a lot of the people that are working on the environmental crisis right now are working on solving it. But there needs to be a group of people who are imagining what life is gonna look like after the crisis is over, especially people who look like me.

AGT: Is there a way that this informs just your day-to-day, the way in which you approach life, which then could ultimately inform more works that you would create? Even if it’s outside of this expression, you know?

BA: I mean, my life is my practice, right? So there’s a give back between like the aesthetic and then the practice of making art and how I live my life. One example is maybe six months ago, probably more, where I was using my body for a reference. I understand anatomy and I noticed that I did not have a muscle where there was supposed to be a muscle. So, I was like, I gotta get in the gym. And since then, I’ve been working out and training myself so that the work is informed by things that I can do.

I don’t think I want to get to the point where there’s an image in my work that I can’t do myself because the work is supposed to be an instruction set from the material choice to the imagery. Like there are instructions laid out because one of the things I think a lot about is archaeology and how in particular for like textile archaeology, you can look at how something was made. And if you have the background of knowledge you can figure out how that particular thing was made. So if someone were to look at my work, I want them to be able to make inferences about what is happening right now. So, looking at the fact that I’m using indigo as a material and hopefully my writing is paired with it so that they understand that this material was chosen because I view it as a material that could exist in the post-climate crisis future. Most of my works are done with nui shibori, which is a stitch resist technique. And like I chose that particular technique because it’s super accessible. All you need is a needle and thread and the fabric or the textile.

In the imagery I’m using, I chose capoeira for one of my works because capoeira was a martial art that was developed in secret. And it’s also simultaneously a dance. So it has that dual aspect of expression: securing one’s freedom and self determination. I chose ballet because I have a personal connection. I didn’t do ballet, but I worked in a ballet studio for a long time. I saw how that was an art form that for women was very healing.

There’s this one piece I have called “Do that lil dance You be doing” and it pairs two different forms of dance. The one [of] the figure on the right [is] pulled from someone, a boy, who is dancing to go-go music. There’s certain styles of dancing to go-go. Some people, will focus on “beating their feet.” Other people will do the contortionist thing like that. That contortionist thing is seen all throughout America. I don’t know, I don’t understand why that particular movement traveled, but it did anyway. On the left is, again, capoeira. So I’m putting these two movements in dialogue with each other to be a conversation about how intergenerational dialogue is important and like there’s something that the older generation could learn from the new. But at the same time, there is that being in dialogue with that older generation and what their movements are does provide a foundation for what it is that we’re doing. Those two movements, the older one is a martial art, like it [is] specifically for warfare, specifically for self-determination, defense. And offense. The one on the right is expression.

To answer your question, I would say my daily life practice would influence my art more than my art influences my daily life practice. I’m very disciplined. Like, I wake up at five, I immediately start writing. I write out my dreams, write up the previous day, and then whatever thoughts come out after that. I have like a whole system with like three or four different journals that I process my thoughts and then I’ll pull out some of those thoughts and either put them into an extended paper, or it’s into a visual medium.

AGT: What was your childhood like in terms of the arts? Was [there] a formal introduction to it?

BA: First and foremost, I’ll say that I did not know having a career as an artist was possible, probably until like 2019. I’m gonna take it back just a little bit, before [attending] Howard. I had no idea a career as an artist was possible. I think that even then I did not recognize my mother as an artist until I started pursuing a career as an artist too. Because I don’t necessarily ascribe to a particular medium, I really ascribe to the idea of being a process artist. And those are the kind of things that my parents showed me. My mother is someone who, once she gets an idea, she’ll execute the idea and then she’ll drop it and then move on. I feel like I got [her] understanding of fluidity in living and I didn’t call it a process at that time, but that was her process of moving through ideas, doing what she wanted to do. For my dad though, I was going with him on weekends to go fix up houses and do handiwork. I learned how to fix things from him. I learned how to work on cars from him. And so most of my physical “making” skills tend to be around building structures, which in a theoretical sense influences the way I view my career in general.

The first thing I can ever remember making was my own clubhouse. Then from there, it was like building my mother furniture for Mother’s Day. I really focused on creating as a utilitarian thing. I didn’t really call it design at the time. As someone who is in the dual space of artists and designer, some of these titles, in particular, for black people don’t describe it as such. I can call my dad a designer, but he wouldn’t call himself that. And so it’s difficult for someone to imagine themselves in a particular space if the language isn’t being used to describe what it is that they’re doing. And like, especially in the design and art space, there are these invisible hierarchies of what particular methods are useful.

AGT: What were those things that brought you to these moments now?

I transferred from Morehouse, moved to Howard, [and] ended up being around the community of artists there. I really got in touch with them during the Howard takeover of the A-Building. They were painting these protest signs. And then one person in particular made like a sculpture of the Founders Library on fire out of cardboard. I was like “damn, that’s dope,” [and] started hanging out with them. I entered the art world more so trying to support them. I kind of saw myself as someone who wanted to be a philanthropist in the long run. I come from entrepreneurs. I was looking at the artists that I was around and I was like “you know, you all are kind of missing out on the business side of things a little bit.” Then I would make suggestions, but [they] wouldn’t be taken. And I was like, you know what, maybe I’m thinking of these things because I have to do it myself.

So around that time, I had been painting as a way of journaling. I would write on canvases and then paint over it. Just as like a mindfulness thing. I think the first step I took into that was to curate an exhibition in DC. And it was an exhibition/installation. So, it no longer exists, but there was an African German school and atelier over by Rhode Island Avenue, next to this church that I used to go to, Greater Mount Calvary. And so I went to them and I was like “hey, I’d love to carry the exhibition here.” I was like, “I’ll pay you all, I just want to use the space.” There were drums lined up all along the walls and we hung people’s art. I had that exhibition [and] that was great. It actually served as a fundraiser for a nonprofit in DC, Art Enables, which is a nonprofit that supports neurodivergent artists. And that was important to me because my brother is autistic. And then I’m also on the spectrum, but no one would really be able to tell unless I talked about how.

So from there, I was painting a bit. And around junior year, I was trying to figure out like what it is that I wanted to do. I [had] just finished a fellowship at Johns Hopkins at the Berman Institute of Bioethics. And by that point, like I knew I wasn’t super interested in the medical field and I wanted to put my attention towards something that was related to environmental wellness and health.

My room is like a really good representation of my mind. I like the idea of how a lot of people who are considered thinkers would have sections in their homes. The easiest reference is how like Einstein would have stations where he would do one thing and then when he got over it, move to the next. So in my home I would have my desk for work assignments. I had my DJ equipment. There’s a section for my painting. And then [one] for like fashion.

I knew I didn’t really want to go into academia anymore. DJing was cool. Like I did that to pay my way through college. But I did not want to be in the party scene for the rest of my life. I did not know any career artists. So I was like, painting is cool. If I sell a painting here or there, like, it’s fine, but that doesn’t make any sense. And now, I was like, fashion. Fashion would be great. I did not attend fashion school, and that is a craft that I do respect. People spend their entire lives learning how to do something. And it’s not that it was too late but I was like, I don’t think it would be a good idea for me to jump into it without teaching myself something first. So I looked at fashion. I was like, well, I wouldn’t design the clothes, but the thing I like about fashion is texture and color. And so I started researching textiles and figured I could approach textiles from an environmental standpoint. So come to find out textiles is like a really, really big field. I could have either gone into more fiber-based work or dyes. I was like, you know what, I’m really interested in water security so we can focus on dyes.

I was imagining this idea of if I were to design something for the post-climate crisis future, like what materials would I use and what techniques would I [use]? And it came from that environmental standpoint of a lot of the people that are working on the environmental crisis right now are working on solving it. But there needs to be a group of people who are imagining what life is gonna look like after the crisis is over, especially people who look like me.

I interviewed 250 people over the course of two years just trying to figure out where I fit in. By senior year, I was applying for some fellowship and my advisor was like, “you should apply for the [Henry Luce] scholarship, it’s a bit more aligned with what you want to do, but it’s only in Asia.” I was like “no, I don’t. I could visit Asia, but I didn’t think I wanted to live there.” But come to find out it was the perfect opportunity. I applied for the Henry Luce Scholarship under the context of someone who’s interested in the environment. So there was design, there was art, and then there was the environmental—which I thought was going to be more academic.

I began thinking about my death, and then how I want to imagine my funeral. Because when I was younger, my grandfather passed. We went to a funeral parlor that was the size of Cramton Auditorium and it was full. That had a really profound impact on me. Afterwards, my dad pulled me aside and was like, “you know, you see all those people who are out there, like every single one of them loved your granddad and had something positive to say. Each one of them had a story to tell about him. He may not have seen some of these people in years but they showed up for this one moment.” From then, I was like, all right, like “what do I want my death to look like? What do I want a funeral to look like?”

I intended on going to Japan to learn this one particular resist technique called Katazome, which is a rice-paste technique. At the time I was doing a lot of line drawings and I was using like the smallest print I could possibly find and I wanted to be able to transfer that onto a fabric or onto a canvas. There are only two techniques that I could use to do that at that level of detail. One was Katazome and the other was a dyed printer. In thinking about that, I was in between two techniques that were like traditional and contemporary. That’s like the foundation of my thought at this point.

Before I ended up getting a scholarship and right after the interview, I flew to Mexico City for a textile artisan conference where Aboubakar Fofana was presenting his work amongst other artisans. I wanted to go meet him in particular because he was the first like black male dyer that I had come into contact with. He is like master among masters. He got on a panel with like four other indigo dyers. And when he was describing what he could do, everyone else was on the panel was like, “damn, you can do that?” He talks about being able to pick a color out of the sky and immediately go get it out of the vat, like in one single vat. Being able to get ten different shades. And on one end of the spectrum, you have like the lightest light blue which like damn near looks white, but it’s still blue. And on the other end of the spectrum, you have a blue black which is looks black, but it’s indigo. One of my goals is to be able to get that color span out of my work. That kind of came from him. I went to go talk to him and I was like, “hey, like, you know, I would love to train with you. I can go apply for a Fulbright, like I can go get funding so you don’t have to pay me like, you know, what do you have to do?” And he was like, “OK, we’re not going to talk about this right now, but, you know, I’m open to hearing you out.” His book isn’t out yet, but he actually let me like sit in front of him and read his book so I could learn more about the philosophy behind dyeing. He has this village in Mali that he’s from where they grow the plants, they do a lot of the dyeing there. He has an atelier in France where there’s a lot of weavers, like he has a system of production and economy around his art. So like combining the thought around Theaster Gates of building of communities, I have this other artist who’s building an economy. And like, I really love that systems thinking. Like that’s kind of what I wanted to study in Japan, the supply chain of art and design. Like how that exists for traditional crafts and if that model can be sustained. Thinking about the supply chain of crafts and the creative economy and a creative economy that’s attached to an expression of love.

The pandemic hits, I’m not able to go to Japan. I had been preparing for it for a while, for months. And they tell me that “Japan is eventually gonna open up, but we’re not sure. In the meantime, would you be able to go into Korea?” And I was like yeah, because at the time we were having the protests here. I was in lockdown in my home and I was like anywhere but here is fine, I’ll figure it out. So I had to really scrap my plan for what I was doing. Ended up meeting, my teacher Haruka, whose mother is the person who reintroduced indigo back into Korea after it had gone extinct because of the second Japanese colonization. Getting to learn from him, learning the philosophy, and him talking about how, like the first dyer was either a hunter or gatherer who stained themselves with a berry or killed something and stained themselves with blood. I loved hearing that. I was like, oh, like, even if that’s not true, that’s a far way to think about it.

AGT: Folklore. If nothing else, man. It’s good folklore.

BA: Right. Exactly. But yeah, getting that theory down, and at the same time, going out to meet Korean designers who are out there. I created a couple of different projects. One was that Creative Economy project where I designed an outfit that was based on traditional Korean garments using indigo. And trying to source the materials locally and then also using local labor and trying to figure out whether or not a garment could be produced sustainably under the conditions. In order to reduce emissions, you need things to be near each other. So I picked materials that were grown there. And I picked cotton. Sometimes cotton is grown to create, but not that often. For what I wanted the outfit to be, which is like a travel outfit, cotton [worked] better than ramie, which is a thinner fabric that’s similar to linen, but it’s grown only in Korea.

I had this one work, “Children’s Story,” where there’s a hand in it that’s pointing, that kind of looks like a gun and a couple other images. And [my mentor] was like, “I’ve never seen a hand in textile work. Like you should explore that a little bit more.” And then I went into full figures. Most of my thought at this time was in the traditional crafts. And the symbolism that they use is nature-based. They don’t include humans in that. And like thinking about ecocentrism I’m like, you know, we need to include ourselves in working with nature. Let me make sure I include that aesthetic in the work that I’m doing so that I can put human life in conversation with nature. I ended up going into full figures and the movement thing. And at the time, I was drawing a lot of butterflies and putting butterflies into my work and I still kind of do that.

That was the time where I started developing my seasonal based work schedule. Indigo farmers were on a seasonal schedule. I came to find out later that in Japan and Korea the way you think about the dye practice is very different. In Japan, the methods are based on a scarcity mindset. They’re on an island, you can’t grow indigo year-round so they dry it and save it so that they can ferment it later and turn it into a vat. In Korea, they only dye fresh, like they pick it off the plant before the flower blooms and they immediately start dying with it. And what they do is that as the seasons change, they switch to other natural dyes because there’s a lot more abundance of plant life there where they can rotate crops or rotate which dyes that they’re using. So [that’s] another thing that got me thinking about the supply chain. There are certain processes that need to stop for a certain period of time and there are some processes that can happen year-round. It depends on the availability of resources and the energy levels.

And I think about that as applied to like my own being. I was introduced to this concept of birth cycles a couple of years ago and the idea is that like while you’re in the womb, you’re conserving your energy, you’re preparing to be born in the months leading up to birth. Birth itself is like the most exhausting act that your body will ever do. Or the most energy intensive act that like your body will ever do. It is literally like moving yourself into the world. That pattern will stay the same for the rest of your life.

AGT: I was really encouraged when I read how you wanted your work to be this form of healing. It made me think about two artists: one musician and one visual artist. John Coltrane, the musician, spoke a lot about understanding the gift that he got from God and that he wanted to use his music to heal people, right? He wanted to eventually get to the place where he would play certain notes that held certain vibrations and people would be able to be healed. And if someone was sick, they would feel better. If someone was sad, they would be joyous. If someone needed money—and not in a greedy way—but if someone was down economically, they would find a way to wisdom to benefit themselves just through the music that he was playing. And then a more contemporary artist Guadalupe Maravilla. He had cancer. He’s a young man, he had cancer and he started going to natural healers within his community who use ritual practices to coincide with the contemporary medicines that he was using. But now he uses sound in his work. So much of the traditional healing happens through sound. What was the process of coming upon and understanding that the healing your work could do? Was it a personal thing?

BA: Actually part of the next body of work is sound. This year, all of my works will be sound panels. If you know about sound panels, they improve the sound in the room. I’m very conscious of those really subtle effects of what my art would do and then it becomes this dual action object of sound art. But then it’s visual and then both are geared towards improvement. I think I talk in stories a little— a lot. But in my last romantic relationship, I told her I that I found this relationship to be very healing. We were having some issues because she was like, “this is really hard.” And I was like “yeah I was healing through this.” And I told her it’s not that I find us being together to be innately healing, but it’s the fact that I’m having to be with you and unlearn certain things and adjust the way I’m used to doing things based on how I was treated or how I treated the person in my last relationship. This is a new person. Through having to make the effort, I have found healing.

I mentioned that because I am very particular about language. I’m not seeking to heal people. I am seeking to use my words to set a space for healing to occur and for people to draw their own inferences with the intention that inference is centered around their own healing. I come from a family of healers and because of that, I have an acute awareness of spotting a sick person. My natural inclination is to not be around them. I may identify it and depending on if I determine if it’s safe or not to engage, I’ll go. I’ll give them the medicine bag and then I’ll leave. It’s their choice to take the medicine. I intend for my work to be that medicine bag, to be those instructions, to be those tools. Going back to the idea of like, you know, shaking out the trauma.

I’m really just about giving tools. I think that part of the imagery that I pick as of right now, like most of it connects with me. The first curator that I worked with on my last solo exhibition, happened to be classically trained to dance. She and I connected [through] the exhibition perfectly. Even in the name of the exhibition, “Dreams of Flight in the Round.” She was talking about how dancers are in the round. And I was like, “what does that mean?” It means that it’s a terminology to describe the fact that the audience is all around the performer. We’re imagining like being in another space, but like using the round as like a transmutation circle for projecting ourselves into the future. My goal with this exhibition is to have even more impactful and more direct connection with the people who are interested and seeking to conduct their own healing and talking to them afterwards or during it, being like, “so, what connected with you?” And then I’d be able to answer this question of what is it in my work that people could read visually or read physically, like actual notes, [for] everything that I’m doing.