by CHRISTOPHER ROBERTS

November 16, 2021

“I want to share my eyes with you, not just have you look at a pretty picture.”

– Tafari Melisizwe

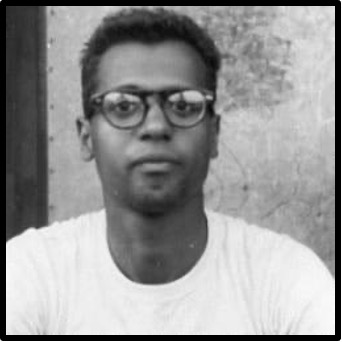

Tafari Melisizwe is Black person from a litany of Black places. From California to Ethiopia to Atlanta to Baltimore and beyond, life has taken him to many corners of this earth. Though he has called many places home at one point or another, at every juncture he has been part of an African world. Melisizwe has shown up in community as an educator, an architect, a researcher, a teacher, and more.

I have known Tafari Melisizwe for quite a while. We met in Baltimore through a mutual friend. The chance encounter would grow into a friendship, and a mutual appreciation of each others’ crafts. Over the years, I had come to learn of his steadfast interest in photographing Black life. So much so was my appreciation of his work that he was the photographer at my wedding ceremony and celebration. In many of his photographs, I see and feel something akin to what Kevin Quashie imagines as Black aliveness. In the book Black Aliveness, or A Poetics of Being, he describes that aliveness as “an inhabitance that runs counter to possessive investments of subjecthood. The alive one does not possess herself, even as her aliveness animates her being in the world.”[1] That aliveness is one of the hallmarks of Melisizwe’s images. His photography does not desire to possess those on the other side of the lens, but rather celebrate that which animates their being in the world, their blackness being a testimony of and to their aliveness. That attention to Black people being alive through being Black is where I understand him to be in communion with many of the Black photographers before him, perhaps none more so than Roy DeCarava.

In a 1972 profile by Ray Gibson, DeCarava is quoted as saying:

“I wanted to photograph Black people, simply because I felt it was ridiculous that nobody was doing it. The only people who were attempting it were white photographers and they were doing it from an exotic or a social sense. I just had this overwhelming urge to say something honest and positive about poor, Black people in the city.”[2]

Melisizwe, is cut from the same cloth, in that he too possesses a relentless interest in making images that say something honest about Black people. To, in his words, “to present black life as it is, as it unfolds.”

Of our first encounter, Melisizwe says that “when we met in Baltimore, that was at the tail end of me going to six high schools in four states, and so I’d traveled a lot, I’d seen a lot.” And it is this “seeing” that has remained paramount in his artistic practice. Tafari Melisizwe has often stated that “I want to share my eyes with you, not just have you look at a pretty picture.” This declaration is yet another echoing of and to Roy DeCarava, who in 1969 had an exhibition in The Studio Museum entitled Thru Black Eyes. Of this exhibition, the first photography critic in the history of the Village Voice, A.D. Coleman wrote that it was “just people, involved in the process of living, unusual only in that most of them are black and have been brilliantly photographed… the people portrayed therein have not been seen as specimens, symbols, or social phenomena.”[3] Coleman portends that part of what underpinned DeCarava’s “brilliant” photography was not just his proficiency with the apparatus of the camera itself, but that skill expressed through his blackness, specifically through his black eyes.

With the black eyes of DeCarava’s approach to photography as a focal adjacency throughout this interview, I wanted to take up Tafari Melisizwe on his offer, and share with us what he sees through his eyes, and not just look at a pretty picture.

Due to me living in Providence and Tafari living in Chicago, we were unable to connect in person. Therefore, we held two separate conversations on Zoom over a period of two days. The first of those conversations focused heavily on Melisizwe’s personal journey to photography along with his sense of politics, art, culture, place and his connections to various Black artistic traditions. The second conversation was primarily about his image-making practice as well as his approaches to craft and technique framed through his own reflections on specific images he has made over the years. What follows is indeed an interview, but also an arrangement of those two conversations, in four parts.

I. Through | II. Shared | III. Black | IV. Eyes

I. Through

CR: When you started this, when you got into art as a thing you wanted to do, did you have these visions of it taking you all around the world, to all these different places that you’ve been? Where did you see it taking you?

TM: Word. Well no…it’s a long journey to embracing, calling myself an artist. I’ll tell you that for for a few reasons. So, in terms of the work itself of image-making, sharing stories about our folks, exploring stories about our folks. Yes, I did see that piece of journeying, traveling, connecting, meeting people, learning, researching, that kind of stuff, for sure. In terms of looking at that through the doorway of like, an artist? I struggled to embrace that for a long time.

I was raised in a household mostly through my mom. Both my parents were in the house, but mostly to my mom culturally. [It was an] African-centered, culturally conscious household. And my mom was the photographer… exploring identity and global black identity. And so that was how I met it [photography], even when I wasn’t really interested in it, per se. Like, I was never “anti” it, I was just 12-13 years old playing basketball and wanted to go do that. My favorite basketball player was Dikembe Mutumbo. My second favorite basketball player was Allen Iverson. I had this plan when I was even playing sports at the time, I didn’t want to be a career athlete. I was like, I’m gonna play for a couple of years, make millions of dollars, retire when I’m like 30 years old, and then fund grassroots revolutionary movements.

As I grew older, [I] started traveling and seeing these things from school and meeting Somalis and Ethiopians in Minneapolis, Liberians and others in Baltimore, rural Black southerners in Atlanta and Conyers, and that kind of stuff. I just got to see how a lot of different Black folk, Black people live. And so, as I graduated high school I got involved in the grassroots organizing community in Maryland, in Baltimore specifically.

At the time, I would have characterized, and narrowly characterized at the time, art [as] like an escapist mechanism. Kind of “we’re not going to deal with the material conditions we’re going to transcend them” and with my upbringing, [I] was like “no, we can actually live the life that we want individually and collectively through collective struggle through collective work.”

I had seen a lot of artists that had amazing cultural tenets, and what I saw were very underdeveloped political and social tenets, and tying those things together. I didn’t want to be that, so I really ran away from being called an artist, in some ways, really ran away from being embracing myself as a photographer. Because yes, this is cool, this is meaningful, this is dope, even. But is this going to materially move the needle for our people, for my people? And the circles that I was in at the time didn’t help give me that room or that permission— that I really shouldn’t have been seeking from them anyway— to really embrace the the value of what I was doing, outside of the typical ways we are socialized to assess value.

I’m not the type of brother that wants to have my artwork on a gallery wall, stale somewhere [that] some middle-aged white people are like, “Oh, this is amazing!” And so I saw it really as an extension and expression of my politics, of my love for African people everywhere and for wanting to specifically know African people and African diasporic people everywhere. So it’s not just this amorphous [notion of] “it’s black people in the world, and I love them.” It’s like… really taking the steps of connection and reconnection, and so I saw it as an aspiration that fortunately I’ve been able to do through most of my work. But again, I think that that was really my politics, trusting my politics, more than trusting my art and letting, really, my heart accompany my politics and interests.

I would keep doing this touch-and-go thing with photography where what was consistent was my politics, my Pan Africanist tenets, my organizing work. What was inconsistent was the expression of that.

Really, in the last two or three years I’ve kind of come full circle again where I was like “no, this is what I love to do.” I’m going beyond this is what I love to do, I can realize the life that I want to live in the relationships that I want to embrace and do and share through this medium photography and art generally. So yeah, I had to decolonize my own relationship to the term “art.” Because at first, I was like “oh you just sit somewhere away from the people, or maybe you take pictures of the people, but then you, you know your goal is to try to be famous.” And I’m not trying to be famous. Unless it’s a Paul Robeson-style of famous.

CR: This idea of the Indigenous Lens that you’ve had for a while now. What is the Indigenous Lens for you, and how does that connect to the sense of Pan Africanism and the Blackness you were talking about earlier?

TM: I think the most straightforward way to talk about [it is] what the Indigenous Lens tries to be. I think it’s a dynamic less than it is a thing. I think it’s a relationship to people and places. In this case, African-descendent folks who assume various identities: Black, African-American, Afro-Cuban, Afro-Brazilian, Pan African what have you.

For people that have seen my work, I do a lot of almost exclusively portraiture, natural light, black-and-white style photography. I have a deep appreciation for all the types of photography but I’ve never really been moved by the high fashion, highly curated stuff. I think it’s amazing, I think people do beautiful work with it, I think you can do powerful stuff with it…there’s nothing wrong with those things. I was really interested in the everyday experiences of Black people’s lives, and the lives that they actually live, not the lives that I thought they should live, not the life that I wanted them to live, not the lives that I hoped that they lived.

So I think, for me, the Indigenous Lens is really just centering and prioritizing the relationship, and the viewpoint of what a lens is, just like our eyes, you know, they are viewpoints. Tools that are used to perceive. It is an intentional spending time with Black people singularly and exclusively in terms of my lens, and my camera, and documentation. It is also… trying to do right by that relationship. I’m not trying to add commentary to what I see, I want to see more clearly. And in that seeing more clearly, which then does… become this reflective thing. I am trying to intentionally share moments, thoughts, and ideas, and conversation starters around Black people and Black people’s relationships to this thing we call life and struggle and movement and just living. You know, in this case, living in the United States, given the particular macro social and political conditions, but also the local social and political conditions, the cultural conditions, you know.

I’m thinking of a Gordon Parks quote that is often used… where he says something to the effect of “the cameras not only just meant to show misery”[4] and I love that because it’s like he’s not saying that the camera can’t show misery. But that there’s a range of human expression and human emotion and human living. People descending from the continent of Africa, we have this varied and shared experience, and I want to understand that better. I want other people to fall in love with that more. Because I think that our relationships are the thing that’s going to get us to wherever we decide to go. On that relationship, and that ground level of what, again, “indigenous” means… we often talk about it in popular culture as meaning first and original. First to what? And so, in this case, it’s an original grounding of like, if I put my two feet here, here I am and what do I make of that, what do I do with that, where do I go from here, where do we go from here? And so for me, the indigenous lens is just that.

Another thing is it is this deeply personal experience, because I think one of the really amazing things about photography, in particular, the style of photography that I enjoy doing is that through the camera I get to share my eyes with my audience. Literally. I’m so not interested in some of the the trappings of adding lighting and making the image pretty, so to speak. Though I do have a particular eye and things I look for… I want to share my eyes with you, not just have you look at a pretty picture. It’s necessary to remember the magic in that. When we’re so pushed through capitalism and consumerism that who you are is not enough at a very basic level. If the shadow fell across your face like that, let me show that shadow, because that’s what actually happened.

I try to do right by those moments, and those interactions and I think that’s what the indigenous lens—in this case understood as my eyes— attempts to do honestly and earnestly without apologizing for the the the fact that. My first, my best, and my work is towards building healing with African people so that we can organize, fight, and win what we rightfully deserve.

CR: You talked about the global and the local. So what are some of these places that have had a real impact on you as an artist, and how you understand or have come into who you are as a practitioner, as a person? You talk a lot about the Black world, or the African world, these different places that you’ve been, you’ve photographed, you’ve lived. You don’t have to give us all the places obviously, but what are two places, maybe one place in the U.S. and one place abroad that you feel has had a significant impact on you as an artist, as a Black artist?

TM: I gotta think about that. And I may take a touch of license to add a third bucket to that question (laughs).

CR: All good (laughs).

Tafari: Internationally, I would say, Ghana. Which of course is so common in particular with Black folks that are in the United States. Ghana registers on our national consciousness far more than a lot of other places on the continent, unfortunately.

I would say Ghana, and this is why. Because I didn’t just go to Ghana. At the time [it was] this blending of work and image-making, I was working with an organization, known as HABESHA, Inc. that still exists. There was a Baltimore chapter at the time that does not exist anymore. I co-directed that and the short version of what that organization did, and does, is a cultural exchange for Black students in the United States and giving them the opportunity to travel to the continent. And why I really loved that work was because, again, this idea of relationship and grounding. I’d seen so much artifice, and so much stuff around like what relations between Black folks in the US and Black folks abroad were supposed to be. You know the common tropes, “Dominicans don’t get along with Haitians,” and so on, all these reasons for fracturing and why it can’t work and why whatever.

And for me, as someone that had, you know, grown up reading studying and connecting with people that were from all over the world, not even just African-descended folks, that just was never true for me. And so HABESHA really gave me a pathway to realize what I had already been seeing in Minneapolis, in Baltimore, in Atlanta. Just like Black folks, “Black folking,” for lack of a better phrase.

So traveling to Ghana, for the first time in 2011. [It] was really an eye-opener. I wasn’t going even necessarily because I needed to have a hole filled in terms of needing the continent to embrace me or this place to embrace me to justify my Pan Africanist bonafides. For me it was, I’ve read about this place, I’ve heard about this place, and I’ve even met people that have been on this side, stateside, from there. And what is everyday Ghana, or Accra, or Bolgatanga in the north, or Tamale really like? How are people making lives in this place that we’ve been scattered from and encouraged not to build relationships to?

I think Ghana for sure, because it’s just a visually beautiful country. And my now wife, who was then my partner at the time, my girlfriend at the time, is also from Ghana. I think what was exciting for me is it confirmed a lot of the continuities that I thought were going to be the case, without sacrificing the very real differences and getting comfortable, getting excited, about embracing the differences. As [Frank] Wilderson likes to talk about, “wallowing in the contradictions.” [HABESHA] was curated in a way that was meaningful, like we’re not just here to show you that Africa has the trappings of capitalism in the West. It was like no, “let’s see how people are living, let’s really connect and commune with people… spend a day being bored in Accra, and see what’s there.”

So I think Ghana, for that and more reasons. But to try to transition a bit, I would say in the United States, I’m torn between Baltimore and Atlanta. And I’m going to I’m going to say Baltimore, mostly because it represented a transformative point in my life. Baltimore is the city that I became a man in, that I transitioned out of being a teenager, from boyhood into manhood. Both in terms of turning 18 but also in terms of assuming responsibility, experiencing heartbreak, working through [different things] I know. [Taking] movement work seriously [and] like having a degree of autonomy.

And in that exploring Baltimore, exploring neighborhoods like Harlem Park, exploring neighborhoods like Woodlawn, and all this other stuff that really gave me, organizationally and individually, the room to meet people, photograph people, document people. Baltimore is the city I began to realize a lot of the stuff that I had been learning. Baltimore was also a hub for me. Because Baltimore is a stone’s throw from D.C., a stone’s throw from Philly. I met Greg Carr in D.C. At Howard, I got to speak on a panel with him. Halie Gerima is very instrumental in my work, very influential in my work, particularly around elders which if we get the chance to talk about that we’ll talk about that. One of my best friends, Amari Johnson, Amari Sekou, [is in Philly] Black Power Media, shoutout to Black Power Media, the new, and the original Black Power Media.

I moved from Atlanta to Baltimore when I was 17 and my experience was living in rural Atlanta, and the suburbs of Atlanta. And not even in Atlanta proper [but] in a place called Conyers, Georgia, Rockdale County where they had a Klan rally on my birthday. You realize real quickly, you step outside the city of Atlanta you’re in the South. As Gerald Horne writes about, Georgia was created as a pro-slavery wall against what was happening in Spanish Florida, but that’s another time, for another day.

Moving up to Baltimore, I got to experience the class dynamics… the material conditions across decades in Baltimore. To see people make life under duress, make beautiful life under duress in Baltimore. In Baltimore, people talk about how people don’t talk about Baltimore, it’s all DC, it’s all Philly, it’s all New York. And it’s true that some of the most vibrant amazing work people, artists, organizers like have both come out have been through and spend time in Baltimore. Until I lived in Atlanta for what was like eight years, [the previous eight years in] Baltimore was the longest place I lived [in one place as a teenager or adult]. So I think it’s those two, Baltimore and Ghana.

II. Shared

It is in that attachment to the people that there exists yet another resonance between Melisizwe and DeCarava. Without equivocation, DeCarava said of his practice that “I’m addressing myself to Black people first. There is a certain responsibility that each of us in his own discipline should survive and help other Black people to survive, and that includes photographers… So that perhaps someone else might go a little more because of us, feel a little more because of us.”[5] Such conviction to both purpose and people is evidenced in the words and images of Tafari Melisizwe. He is moved by a sense of responsibility to and reverence of his people that I hazard to think would bring a smile to the face of Roy DeCarava.

In contextualizing the myriad uses of the camera by Black organizers and activists in the mid 20th century, scholar Leigh Raiford, in her book Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom says “The camera first offered SNCC a way to intervene in dominant media frames, a tool to document its activities with its own consistency of message. This developed into a means of presenting itself and its vision to the world. The camera would then provide a technology for self and communal expression, a way of presenting and representing rural black southerners to themselves.”[6] Whether it was intervention, documentation, preservation, conservation, celebration, or something else altogether, Black people have found many uses for the camera. Clearly positioned as an artist who understands his purpose as being connected to the beautiful struggle that is black aliveness in an anti-Black world, Melisizwe enters into those traditions and trajectories from a particular vantage point.

CR: Knowing that you are a student of Black history in a wide variety of ways, and definitely Black Arts history. Thinking with Langston Hughes’ “The Negro Artist and The Racial Mountain” (1928), and Larry Neal’s “The Black Arts’ Movement“(1968) and the work of someone like an Emory Douglas, specifically ideas of the community and the individual and the role of the Black artist, how do you think about what you’re attempting to do, in relation to this longer history of Black artists and Black arts traditions?

TM: I think [it] comes through mostly through a photographer that I was fortunate enough to work with in Baltimore at the Walters Art Museum, when I was graduating high school, but [now] Chicago-based photographer Dawoud Bey, shoutout to Dawoud Bey. So there’s a book that he that he wrote that I think is super, super dope called, I think photographing people in communities [Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities: The Photography Workshop Series], I have it inside. And one of the things he says in that book just on this, the same subject matter, he paints this picture of artists and he’s talking broadly [about this] long table, there are all of the greats and all of that, and then you look around. And there’s a chair that has an empty seat and basically he’s goes on to say, like how are you [and] how do you want to be in conversation, how do you want to be in conversation? And not so much in the sense of a regimented blending in, but it’s like no, these folks didn’t blend in with each other, and they are part of this. I just want to be in the conversation for one.

I’ll let history write what it is what and what they say, but my hope is that it’s like, “here is a brother that sincerely loved his people and used his talents and skills intentionally to share that love and connected that to principal grassroots struggle and organizing and movement work. And that, as he got older, as he evolved his work changed, but he never left his people.” I think that is probably the key thing.

And another thing, I think this is where it’s really important, for me at least, to embrace being categorized as an artist, but to not get so transfixed on that because I’m also so many other things. And not in the way of accumulation. I do tell stories visually, but I’m also an educator, I’ve been teaching at an African-centered homeschool for the last five years, and as far as I’m concerned I’ll continue teaching. I’m actually getting ready to teach a class in architecture and a social studies class.

I’m also involved with some other grassroots organizing work in some other places. One of the most meaningful awards I got this year was from the Black Alliance for Peace. In the photography world, to get recognized by an anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist organization is not something you put on your CV and go, “hey sign me up for this next bigger thing.” But the indices that I’m looking at are the people and the movements that are involved in the things that I care about [and] asks to receive this kind of art.

In community, I’m like, I’m here. I want to be here, what do you need from me, what do you want from me, what do we need from us? What memories are we trying to create? What stories are we trying to gather? What fragments do we want future and present generations to pick up and run with? And so what do we want our folks to get excited about about the movement? I am in this world, so it doesn’t make sense to me to leave it for anything, and what I mean by that is that, if I’m saying I am, you know, a Pan Africanist, if I’m saying that African people and the world over, deserve to be free from this capitalist-imperialist-militaristic-sexist hyper-exploitative system, then I should arrange my activities towards that end. I should network my relationships towards that end, I should find ways and means sincerely to source my joy and sustenance and sense of meaning and anchor there. That should be metaphorically and literally my home. And that’s true for me and I don’t have to conscript that. So it’s not like I wake up in the morning and I put that on and then go out in the world and make “Black art” or what’s called “Black art” and then come back home and it’s like well you know I really like this [other] thing. It’s like no, this is what I do, this is what wakes me up in the morning, I want to quit the two jobs that I have so that I can do more of this.

And so, in terms of my role, and what I would love to see other artists role kind of embrace is again is just like being in relationship. Not just as an artist. Being in relationship as a person, or however you choose identify yourself like being in relationship to movements and ideas that materially spiritually and psychologically like heal our people. If other people want to comment on my work, whatever. Do the people that I care about validate my work? Now if these other people have the power to curtail my quality of life—like what happened with folks like Paul Robeson and others—how do I reassess and reaffirm and re-engage skills that I may have to forward this work to for this movement to engage the struggle? I think that’s what it is to me. It’s like I intend to be a multi-talented brother, I intend to be a multi talented-person, and I intend to be of service to the movement in ways that are effective, to the goals and objectives of the movement. In movements, I’m not so caught up on myself that I think I know what’s best. Even if I like it, I think we should move in a different way. Again, my goal is to be in community. And if I sincerely believe I’m moving the wrong way, I do everything I can to try to encourage us to move in another way, and if not, be with the people and keep building. Because, as an elder that I know said about one of their grandparents, you know, “all danger ain’t death.” So if we’re going to be in precarious situations, which movement work is going to do, and as a photographer documenting that, I’m active in it. I’m not passively watching the movement, I’m documenting the movement.

I’m just gonna speak for myself now, I will say, I would like to see more of this. If artists avail themselves, if I avail myself to so many other streams of knowledge production of thinking of theory and practice what have you. I read Amos Wilson. I read Quito Swan. I read books like Epistemologies of the South. I read Kwame Nkrumah. I read Dawoud Bey. I read works and writings about Fannie Lou Hamer. I engage in dialogue with people. I read through Ruha Benjamin’s Race after Technology. I read as a strategy to understand and collapse time because I’m interested more so in phenomenal logical time [versus] linear time. That’s what the terrain calls for, that’s what the moment calls for. How dare I think taking images is enough, how dare I not know history? Mumia Abu-Jamal’s ability to produce work, analysis, and ideas [are a] partial inspiration. People like Mumia are kinda like my guideposts. The discipline of deep and rigorous study guides the deep and rigorous study of image making. Because yes, time moves forward, this time passes, but have we moved forward?

To bring all that back, I think, ultimately it’s the role to be in conversation and to be in conversation I think it’s important that I bring the requisite materials for dialogue. I think those requisite materials are: a deep interest in listening, a curiosity about myself and what’s happening, an earnest and honest approach to everything, an openness to being completely wrong, and not being afraid to embrace change and transformation. It reminds me of this capoeira song, Capoeira-Angola, something I practice, an Afro Brazilian martial art. In English, it says, “all that glitters is not gold,” and the second line is “all that moves doesn’t fall.” What I really love about that is it’s like “no, I can take a little discomfort I can take being off balance. I can take being uncomfortable.” Not at the… expense of my life, so to speak, but meaning it ain’t just got to be what I wanted to be, to be. And if I’m gonna be in it, like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o talks about “we got to be here in order to be here” so let me be here, let me be fully present eyes open, listening and in trusting that I have something to offer and knowing that I have something to receive, so let me pass the plate. I’m not just sitting down so that no one else can sit down. Let me, you know, eat from this nutritious meal that’s come before me, and you know extract the nutrients that I can. And the plate’s not empty, let me pass it out.

CR: A lot of Black artists are constantly thinking about relationship to audience, who their work is for. Not everyone is going to be an artist in the same way or be connected to the movement or commercial or entertainment worlds in the same way, but no matter where you land, you are still Black. In the same 1928 essay I mentioned earlier, Langston Hughes wrote “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.”[7]

Though Hughes was writing in the context of a patronage-laden 1920s, whiteness still pervades in similar ways today. With full understanding that you’ve intentionally situated yourself apart from that world as much as possible, how have you arrived at the disposition you have about the specter of the “white audience” relative to your own art? And what words would you offer to Black folk who want to make art, knowing that this white buyer/patron/consumer/audience specter is always there? How do you maintain that connection to the African world amidst the specter of the “white audience“?

TM: In Discourse on Colonialism, Césaire said something to the effect of— to some European writer that had critiqued him—in no uncertain terms that though we may be using the same words, we don’t even speak the same language. Admittedly, I’ll say in some ways I’ve been insulated from that world. I haven’t had to deal with that outside of some small situations, because since I struggled [initially] to embrace calling myself an artist, I’d kind of rejected that whole world. Not even aggressively. So I wasn’t like, “I don’t want to be in your galleries.” I just didn’t want to do so. It’s a two-fold thing, part of it was something I think a lot of artists and makers deal with. The enduring question of “is my work good enough, is it really that nice?”

I’m even thinking of, you know, I saw some of the wedding photos—by the way, happy anniversary to y’all!—I saw some of the wedding photos from y’all circulating around thinking “yeah, these actually came out pretty good.” And I remember shooting there and I remember, like the whole story of how Jon (shoutout to Jon Crisp) lent me one of his lenses. [And when] I saw the images and sent them to you like, I like them, I know you all like them and love them and I think this enduring nagging that is a product of capitalism that tells us that what we’re doing is not enough and that you’re not enough, and if there’s gotta be something wrong with it, or if not with it, then it’s with you.

I’ve really never even really tried to get into that world. [But] I think [there are] two moments that come up for me. One, I went to a portfolio review at MICA, the Maryland Institute College of Art. I was maybe 19 at the time [or] 20 at the time, and I think the department chair was reviewing my work and we ended up getting into a little bit of an argument. She was a white woman if I recall correctly, and I can take critique, so it’s not [that]. She was critiquing my process in a way that I didn’t like. And that’s when I started to learn about the business of art. Because when I started shooting I had no formal training, I took one photography class in high school. Everything else was—before “YouTube University” was a thing—it was books and people I know. And trial and error, and hours and hours on Photoshop stumbling through things and learning things and all that kind of stuff and loving black people. And I remember her telling me that you know “it looks like you’d like to do a lot of things.” She was navigating through the pages, and “that’s not what we’re really looking for here.” Like you know, “we want folks to really focus on one particular style and then move forward in that way.” And I was like “well, I hear that.” My understanding of a portfolio is also to show one’s ability to do multiple things, since the call didn’t say we want to see this particular type of artwork. Then I said okay “well, let me put together an array of work that I’m capable of, and if you want to see more of a particular style that I can go grab those things.” And she basically was like you’re foolish for thinking that. And I was like you’re foolish for saying that because that’s not what real people want. I was just like this ain’t the place for me, I can get “maybe your lighting is a little off here, this could be sharper, this could be that.” That, I could do. But this idea [was] that you’re wrong for entering this way. I might have been born at night, but it wasn’t last night. And I started to learn that photography school teaches most people how to do what most things under capitalism teach you how to do: reproduce an understandable, logical model. I’m not knocking people that go to photography school or architecture school or whatever, it’s a way to learn how to do things, not the way or the singular way. And so I was like “thank you, very much.” Unless someone’s foolish enough to give me a scholarship to go to school, then I’m not about to go. I’m not about to go pay for this.

And then there’s another photographer, Sheila Pree Bright, that’s based in Atlanta. Most of her work is around the emergent hip hop in the 90s and Houston. Super, super dope sister. She put me on to Magnum, which is really well known. She was like “you know I love your work, I told them about you.” There was some social justice fellowship that they were doing. I went back and forth on it for a little while. I was grateful that here’s this well known photographer that’s talking about my work. It sounds exciting to be able to fellowship you know, maybe get some career traction and blah blah blah. And then it’s like, is my work really good enough to do this? Then it flipped, and was not am I good enough to do this? It’s like, is this even where I even want to house my idea? Do I really want Magnum to have my stuff? Is this this the space where I’m going to have the most likelihood of [the] Black people that I want to see my work, see my work? I didn’t have an answer for that, so it wasn’t like, no let me not do it. I was like, I don’t know. So, I applied. I didn’t get it.

I took it on the chin. I was sad for a moment and but then actually after some time I was actually glad that I didn’t get it. Because I was like, I don’t want to be known here. And I know people who work at Magnum so it’s not anything like that. “Tafari Melisizwe, the Indigenous Lens, Magnum photographer.” That’s not how I want to introduce myself. I’m glad we’re having this conversation. I’ve been planning to write about that, about why I’m glad I got rejected by Magnum. Not even to knock them because it’s not about them, they’re going to do what they want to do, regardless. [The process made me ask myself]: Am I trying to speak to the application or to this amorphous list of your demands and styles and preferences? Doing it for survival is understandable, I’m not knocking anyone, not telling people not to survive. I’m not too good, it’s not that. [For me it’s about] to what extent if we say these things are problematic, to what extent is it imperative that we really just don’t participate? Do what Miles Davis did, just really turn our back and deal with the scares, the unknowns, the struggles of that construction work, the risk of “yeah this may all fall apart.” This may not work along the way to something working. [At this point, for me, it’s become about] taking yourself seriously as an artist in ways that are meaningful to me. Taking some of my work and putting it together and wanting to publish some of it, putting it in a few places, putting together some themes, entering some photography competition competitions and all that kind of jazz.

I think, “what’s my my North star?” My guiding compass, or what have you, is making sure that I always remember where home is and where home is not. I can walk out my door and go engage the world, but I’m clear about what home is and what my home responsibilities are and if something threatens those home responsibilities, like, that’s a non-negotiable. If you’re not clear about what home is, you will have made this [other] place home. And [for example, speaking to other black people] “you’ve gotten really skilled at crafting arguments and stuff to try to convince white folks to do something different, while at the same time, your skills of connecting with Black community have atrophied.” Because you ain’t spent time there. You spent time here. You ain’t worked on developing your skills. You didn’t think you needed to. And at the time you didn’t. But now, it’s 95% of your time is here. 5% of your time is [with Black people].

Get clear about what home is, and what home isn’t, so that when you engage these spaces, your sense of okayness isn’t adhering to what happens here. Doesn’t mean that you don’t want it to change. But if it doesn’t, you are not questioning yourself. Because you have another place to go to when white folks, or when capitalism capitalizes. [A place] where you cannot just get recharged, but reaffirmed, and also spend your time because that’s where you need to be. So I say that as a metaphor for the art world, I think for me it’s important that I’m clear about where home is and where home isn’t. It’s important that I can step outside, engage the world, [and be] clear on what home is.

I trust myself, so who I am to you, it’s what I’m going to be with Magnum [and] with who I’m going to be with whoever, with who I’m going to be at an art show— with who I’m going to be. My work is going to be an extension of that. In the same vein, I don’t see it as necessary for me to… I don’t need to comment on every interpretation of my work. I want you to know what my thinking was about my about what I made. I don’t want you to guess, because you can only guess so much anyway. Why I asked someone to stand here or there, what the weather was, what my thinking was when I approached this person? You can’t know any of that, so don’t try to. Now you can personalize, [say] this is what comes up for you. You can say I don’t agree with it, and here’s why. But don’t say what Tafari (or anyone) really meant. I mean you can do it, it’s just disingenuine.

The only advice I would say or offer to people that are not wanting to aspire to navigate anywhere really not just the art world is get good at trusting yourself, and get clear about what home is for you what constitutes home, be clear about those two things. For artists that identify as Black or identify as caring about Black people, live a life that cares about Black people, don’t just produce work that cares cares about Black people. I invite folks to think about doing that in everyday ways. It’s not a performance, it’s a life. It’s not a TV show, it’s a life. It’s really about the experience. And have a good time, but not at the expense of anyone. Don’t be so holy that you can’t connect with your people. And that’s okay, you can still be with your people, if you decide that they’re your people. Avail yourself to the possibility that you ain’t the only one that got something to offer.

III. Black

Roy DeCarava may have described photography as an “intransigent medium” but nevertheless he strove to use it to “get at what you feel.” He wanted to “reach people inside, way down—to give them a quiver in their stomach” clearly not seeing “art as an individual function as much as a social function.”[8] Yet another array of perspectives that he shares with Melisizwe. And in order to elicit that quiver, DeCarava exuded a consistent discipline (or principle) when it came to his work with the camera.

A.D. Coleman captured DeCarava’s discipline (or principle) when he wrote that, “one is conscious of him not as a photographer, but as a perceiver, focusing himself on the world, forcing the viewer to experience it with him, up to the hilt. Discipline and freedom, eloquence and understatement, in exactly the right proportions — the hallmarks of a consummate artist.”[9]

To Melisizwe, the right proportions are about a balance between joy and struggle, between black and white and gray and other colors, and between images and knowledges. For him, it really is a matter of that balance being “what the terrain calls for, that’s what the moment calls for.” Elaborating on balancing the demands of the terrain he says “People like Mumia are kinda like my guideposts. The discipline of deep and rigorous study guides the deep and rigorous study of image making.” The consistent discipline (or principle) that drives Melisizwe’s artistry guides his image making generally, and his choices as it relates to the presences and absences of color in his photographs specifically.

CR: What is your relationship to black-and-white photography? What is your relationship to color in photographs? How do you see color in the work that you do? Colors including black and white.

TM: I dig it. Great question. Beginning in photography—that was in Mrs. Muse’s Woodlawn High School photography class—I learned photography through film and film photography. So before I get into color, I guess, I want to talk a little bit about time. What I appreciated about learning about film photography was the constraints it puts on the media. In today’s microwave kind of image society—which I’m not saying it’s good or bad— I think there’s a lot of excess and I do think that there’s an opportunity to do some things slightly different. We’re producing in a different time.

The constraints of [knowing] I have 36 images or 24 images on this reel. And I don’t have the ease [of a digital camera] with dual card slots that can house 7500 images (laughs). The timing of [being] selective with what I see, and selecting what I document, was what took me to really loving the colors and gradations of black-and-white photography. I’d read Gordon Parks’ book Choice of Weapons. He did a lot of documentary work in black-and-white and in color. A lot of his black-and-white images [to me] really gave off a sort of timeless energy, and I liked that, since I was coming to photography primarily as a doorway of exploration and commentary on social, political, racial and community issues.I was really interested in how can I filter out all of the distractions to really, really get into the content and the context of the story, or what’s present there. Black-and-white, and really gray, because if we’re talking about black-and-white, we’re talking about grays. [They] really, I think, simplify sight. Which allowed me, gave me room, to see more deeply into what was present

And I love, I love color. What I noticed early on when I would share my work [in color] I wasn’t getting the conversation I wanted. [I wanted people to see] the form and the structure and the gesture and the moment that actually is being there. It’s not one is better than the other and do we do receive these things together, and more and more consistently as I started shooting more black-and-white work. I heard the conversation change around how people were seeing my work and others work and of course I started reading more on black-and-white imagery and psychology.

I see in full color and those kinds of things. When I’m behind the camera, I almost see people in the world in black-and-white. Not in terms of a reduction or simplicity, [or a negation of] the spectrum of who they are. It’s kind of difficult to explain neatly, but I see in black-and-white and gray. To me it’s the truest representation of what I’m seeing when I’m making images. Since my photography is so much of seeing people. Trying to get at their essence, or what I see as their essence. Colors outside of black, white, and gray, for me, are like the special seasonings, but/and I love cooking simple meals. Because I think they’re easier to digest and in that they can dig a little more deeply into what’s there. And I think that’s what my photography work really tries to do is look mostly at what’s there.

CR: There is some discourse out there about the colorizing of historic images, and black-and-white being dated. Sometimes you’ll see these comments sort of offhand about “you know they put they put these photos of black-and-white, to make us think it was so long ago.” There’s this idea that sort of color is what makes it not that long ago or current. What is your sense of the idea that black-and-white keeps us at an excessive distance us from the past, or do you or do you not see it that way?

TM: I’m continuing to embrace considering myself an artist, so to speak, so there are lots of contemporary conversations I guess I just don’t know about. But I definitely have thoughts about it. I’m intrigued by the conversation. African indigenous peoples have been working in color and black-and-white, as long as color, black-and-white and African and indigenous people have been around. I think about the time I spent in Ethiopia and in Ghana, and studying history just looking at the intentional use of color. Sure, the technology and digital imaging and film imaging and color is relatively new. And yeah to me, I just think it’s more, why settle on it? I think it’s more of a stylistic thing than a commentary. It [colorizing images taken in black-and-white] is almost embellishing what we already I think tacitly accepted as the myth of image making to begin with. And what I mean by that is, I can take an image of let’s say, Satchel Paige, or let’s say Jack Johnson or let’s say… I know there’s been some of the popular images of [Marcus] Garvey that have been recolored and that kind of stuff. Wonderful. And, we don’t know for sure if those are actually the colors. I would say, do we need to? And, if so, does it fundamentally change the content of the material content of the image, the material context of the image? I also am of the mind that I think, you know, there’s an important rift, I think, to make at least in my own work, about disrupting this notion of endless linear progressive time. It’s not an enjoyable continuity, but at least for me, the value that I got out of black-and-white imagery of yesteryear. Social justice protests and movement photography is contemporary.

I’m thinking of the image of Devin Allen’s work that made Time magazine in Baltimore a few years ago. Another photographer, Sheila Pree Bright and her work #1960Now. I think there’s a tacit understanding… an acknowledgement that things really haven’t changed. I would probably say there’s some ideological consistencies, too, with wartime photography. So I think about [it] phenomenologically, the the consistencies of settler colonial domination state-sponsored terror, of systemic deprivation of police brutality, of violence. I think that those things are consistent expressions… [and] so I think it would also make sense that the imagery around those things remains eerily consistent. Again like I said, it’s not an enjoyable continuity, [but] I think the continuity makes sense. Color is in some ways embellishing what we already accept.

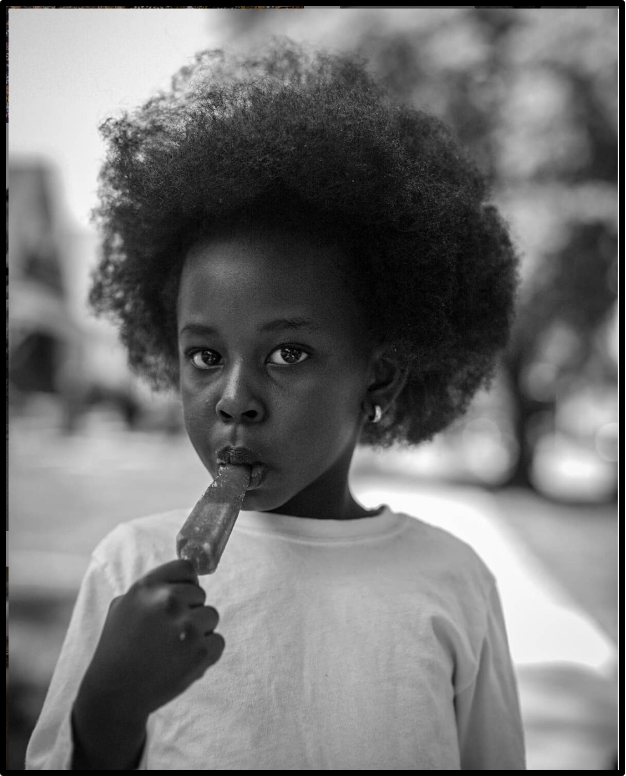

CR: I wanted to follow up on something else that seems fairly present in your work, children and elders. Both seem to be a point of focus a lot and show up a lot. Is that something you set as an intention, to view these different poles of our community? Is that something that happened organically, or do you see it in another/different way?

TM: I wish I had a more sophisticated answer (laughs), but I’ll give you an honest one. Haile Gerima told me to document wrinkles.

My grandmother lived with us for a little bit, when I was six or seven years old, she passed away when I was nine. My grandfather, by the time I got to know him, had dementia, so every time he met me we were meeting for the first time. I didn’t feel that as a loss, I knew I was loved and I knew that people loved them.

Some of it may be, in an earnest collectivist sense, [that] I see elders as people that have seen a lot, been through a lot, and lived long enough to see them, and see the other side. There’s a large repository of experience they embody that I am in love with. There’s so much wisdom and anecdotes in those stories. [And] there are a lot of stories that get lost if someone is not famous. I’ve always been more mature than most people my age, and I’ve gravitated toward elders. When it comes to elders, there’s still ways we can commune with each other.

As I grew older, I started doing a lot of work with young people, especially teenagers. A lot of people are [unfortunately] afraid of teenagers. There’s a lot of conversation about teenagers, but not a lot of conversation with teenagers. I approach everyone like they’re people.

I think elders’ smiles are incredibly honest, children’s smiles are incredibly honest. I think the sense of wonder children have about the world is something I keep. I think those two categories of people really excite me, and have aspects of myself that I want to maintain across time. I always want to be youthful, elastic, open. I also want to be able to trust what I’ve seen, stand on my square, and make decisions based on my experiences. I also think about the work of Malidoma Patrice Some, and Sobonfu Some, when they talk about how in their cosmology and sociocultural framework, to paraphrase, “The elders and the youth are the closest in age.” [To me] they’re saying that the elders are close to going to the ancestral realm and the youth have just come from the ancestral realm.

CR: Do you have a type of camera that you prefer to work with now? Are there any cameras that excite you, or that you’re interested in using? Has that changed from Mrs. Muse’s classes to now? What do you get from the process? And what does the process give you?

TM: As we have this conversation, I think about capitalism.

CR: You don’t have to drop no names (laughs).

TM: I will say that have no brand allegiance. I’m kind of a utilitarian in the sense of if it works for me, I’m going to go with it. And I do think it is important, it’s the tool that I use in my arsenal, the toolset so [to] speak. I think, [it’s] important to me that I’m conversant in what it is. So yeah, the first camera that I had in Mrs. Muse’s class was actually a camera that my mom had. The first camera I had was a Pentax K1000 (or K5000). I don’t have the camera anymore. I graduated high school and I knew that I wanted to get into photography, [but] didn’t have a camera. I didn’t have a digital camera and time this is 2008. But I worked at a pizza place, Ledo’s pizza.

CR: The one by Security?

TM: Yup, the one right by Security. (laughs)

CR: By the blue church? (laughs)

TM: Yup, exactly. I went and I had a plan. I said, you know, I’m going to work here for six months, say, but get a camera. Huge shout out to my my old AP British Lit teacher Akita Pearson. I would be in her class like “bump British literature, it’s colonial, why do we need to read about Geoffrey Chaucer?” I didn’t make a secret that I wanted to make images. She came and would [financially support whenever she was] at the restaurant. So sure enough I saved up, got a camera, quit my job, and that was a Canon. I still have the body of that camera but it’s it’s it doesn’t work anymore. That was my primary camera for a number of years. That’s the camera that took me to Ghana, Ethiopia, to shoot your wedding in Jamaica.

And then, for a while I was shooting with a Nikon I don’t remember the brand name or the model of it but it’s because a friend of mine, Ahmad Abdullah, let me borrow his Nikon for like six or seven months. And so that allowed me to, you know, keep making images. I’m just forever grateful for that friendship that I still have.

I did a bunch of research into cameras, for years, but for a long time, I just didn’t have the money to get the cameras that I wanted and, of course, because of capitalism there’s a new thing every week, [a] new thing every year.[It was this] kind of dance between prioritizing photography and prioritizing other things, I was slow to invest in the camera. Now, for the last four, five, or six years, I’ve really loved what FujiFilm has done. As a really good elder, Baba friend colleague of mine put it, their film “actually knew how to take pictures of Black people, of people of color. [Whereas] for Kodak, the baseline was white people.”I shoot now with a camera called the FujiX-T3, a mirrorless camera. It’s a digital camera with all the trappings of a digital camera, but they design it like an old school SLR. It’s a very tactile camera and I like that. A lot of newer cameras feel to me like computer programs that happen to take pictures. Fuji are typically less expensive, excellent quality. Most of the image making companies borrow heavily from each other anyway. It feels like an old school camera. And it’s small.

Photography is such a fascinating medium, I literally get to share my eyes with people… what I see everyday. A lot of my work was candid, and still is. I think moments are really special. Photography is a beautiful way to see. It encourages me to slow down, to take the time to see. [With film] I have a finite number of images on a reel, it encourages me to be selective with what I’m filming. Digital photography allows me to snap, and see if I got what I’m looking for. A lot of my work was like, “I’m catching the bus, catching the train, or walking through a neighborhood.” I would take time to be in that space, and based on what I saw [I would take photographs]. My process has evolved across time. I think I’ve become more interested in situating my images in more intentional conversations and intentional commentary. More project based photography, but still [with candid in mind].

I think about something that Haile Gerima has said before to me as well, he said to a group of youth I was working with at the time: “You all are only entitled to making new mistakes. You shouldn’t be making the mistakes we make, you should make new mistakes. If that’s the case, that’s our fault. Not saying that you all can’t make mistakes, but you should be making new mistakes.” My process of image making connects to what new mistakes can I make in photographing black people. My work is honest but it is not objective. I’m not an objective person documenting objective realities. Not just [to] critique [the times], but participate. Image-making is a strategy for getting your attention, and once I do, what do I want to say?

IV. Eyes

Dawoud Bey, whom Melisizwe credits with imparting wisdom to him years prior, said in 1979 of his Reflections of Harlem in USA Studio Museum exhibition: “These photographs and the experience of making them was for me a homecoming of sorts… It is in those relationships and the lives of the people that the deeper meaning of these photographs can be found.”[10] In some ways, it is in the viewing of Melisizwe’s photographs that one is taken back to one home or another. The relationships between and among those present in the image belies a connection not only to the moment that was photographed, but to a more capacious black collectivity.

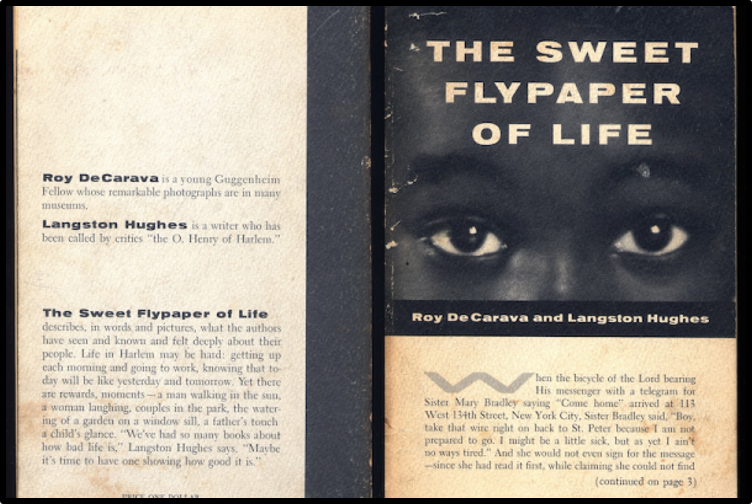

In their 1955 co-authored publication, The Sweet Flypaper of Life, Langston Hughes and Roy DeCarava assembled a symphonic visual masterpiece, arranged with Hughes’ words and DeCarava’s photos to compile a concert on paper with images and letters serving as the notes.

One passage that spans a handful of pages, harkens to—or foreshadows, rather—Tafari Melisizwe’s work: “Some are out looking at parades: Some have been where they are going. And some can’t make up their minds which way to go: And some ain’t going no place at all.”[11] In the photographs that accompany those words from Hughes, we are invited to share in DeCarava’s eyes, and the eyes of those in the images. We are invited to wonder, where have they been, where are they now, and where have they yet to go, if they have anywhere to go at all?

Similarly, Melisizwe’s photographs share with us a type of sight, a sight that is only visible through black eyes. And it is that sight that I wanted him to tell me more about.

CR: It would be great to hear you talk about a few photographs. With each of these, tell me about the photograph. I’ll keep it that open-ended, whatever you want to say.

TM: This is a great place to start. I actually took this image right outside my house. This is my daughter. The image was taken in June of this year, my first full year living in Chicago. As the summer started to come on, we started diving outside a little more. We would just hang out on the front porch, and just spend hours outside playing games, kicking a soccer ball around. Our primary base of where we do things. My daughter loves afros. This particular day she was rocking her fro. I remember looking at her and thinking, “wow, look at this beautiful, carefree child.” I didn’t pose or guide her in any way, I just asked her to look at me, and I saw this. This is what I saw. Reminded me of some of the images you would see in urban centers in the 70s, 80s, and 90s.

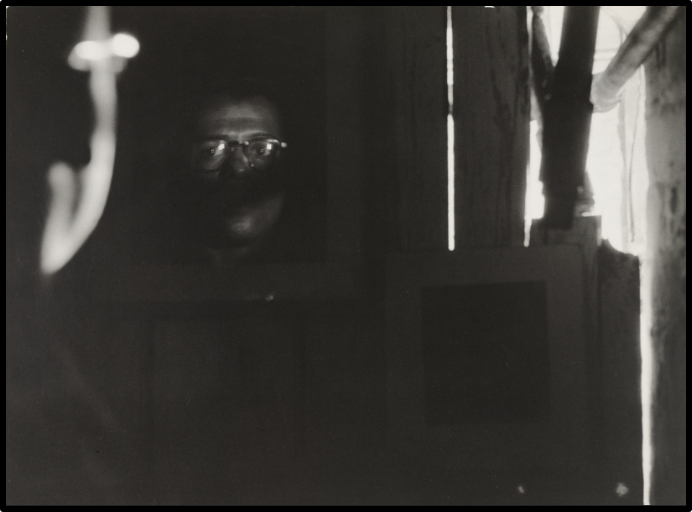

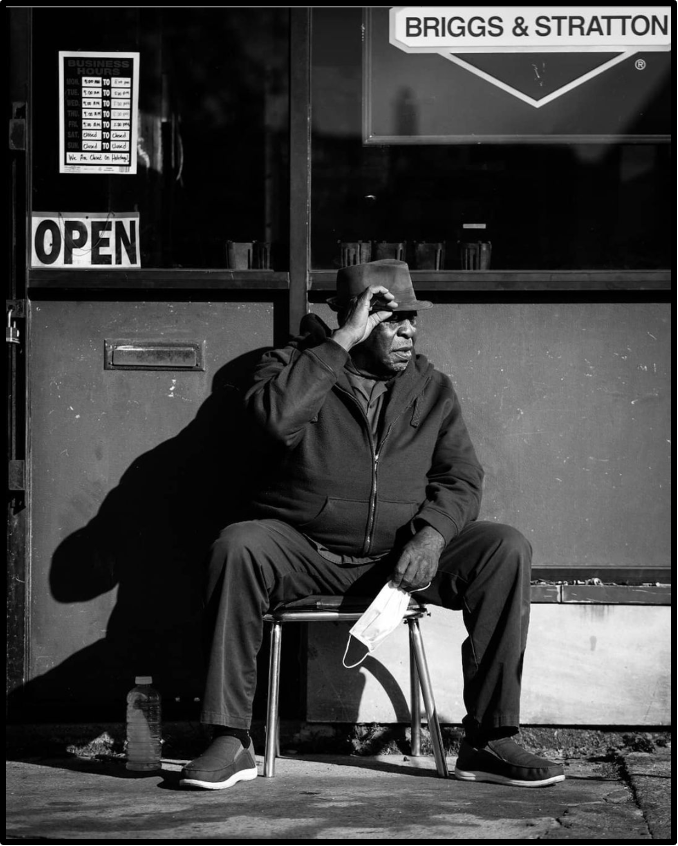

I had just moved to Chicago, my then girlfriend (now wife) used to live [in the area]. During my trips here I was so in love with Chatham. [It] was the site where a lot of stuff went down when [the] George Floyd protests went down. It’s a lively place in [all the good and not so good ways that can be]. Chicago brothers just have style. I just wanted to turn around and ask him if I could make a photograph of him. They asked “what you gonna do with it?” I never question people’s apprehension of being photographed. When I snapped a few pictures of him, this is what I saw. I was slightly disappointed with how these came out, the shadows are a little bit harsher than I wanted. I want to shoot in natural light, so I’m always working with [and] making the best of what’s there.

I love being a Black man. I really love Black men and Black boys. I didn’t do typical mainstream performances of performing Black manhood. I had a few experiences with brothers who did emote like me [and saw] here’s a different example, here’s a different relationship. Part of what I love about documenting Black men is that I’ve gotten more comfortable [accepting] myself. [I want to] contribute positively to sharing images of Black men as themselves. To say, “I see you brotha.”

Amari Rebel, Amari Sekou. Incredible husband, father, best friend. I’ve got to see his work as a musician evolve. He’s my friend. One of my best friends.

Why did I publish this image? What I love about it is the mood of this image? It is a soft image, it’s a hazy image. He is a student of Jimi Hendrix and Bob Marley and [those resonances] are definitely here. Both get reduced from the visionaries that they were. I think Amari shortchanges himself with how dope his ideas and his work and his organizing and activism is in this medium of music. I think this image shows him as a skilled person in all of those areas. Amari didn’t just pop on the scene and decide to play music, he’s really put in time and practice and study. Genealogy of a Soul Rebel, there are lives that contributed to his life.

I really love architecture. Architecture has a lot to do with both of these images. The name is inspired by a capoeira Angola song “All that glitters is not gold, all that moves doesn’t fall.” This is a sister I know, Danielle. There is this sort of theatrical and musical notion of witnessing us that is really amazing to me. I am consistently amazed by light, by African people. Not in the political formations of what I’m saying, but the mechanics and psychology of sight, of seeing us. Chicago is really what birthed this image style for me, there’s a lot of open space here. The terrain is [a lot of] the built environment and the sky.

I’ve thought about this park and this place, and this deeper appreciation for what I’m able to see. I really like looking at Black people in space. Black people are in the future, Black people are in the present, and Black people are in space. “Dig your hands in the dirt.” Looking at the world from that perspective and that space. Some of the beauty of capoeira Angola is “even when I’m off balance, I’m not off balance.” We train about getting comfortable in uncomfortable situations. “Making a way out of no way. Making a dollar out of 15 cents.” I thought this image was dope because here’s this Black woman I met, and when she stands on that rock, there’s something about you and being in space that looked amazing to me. As a symbol, as an avatar, but not as a spokesperson. Even as she’s there, she’s in movement. Geopolitical forces are moving, and here she is.

The end of an Oshun festival. I had just met Solange, that was cool. I remember looking off, I think to my left, and I just saw this cyclist by themselves. At this point, the noise of the day had gone, the drums had left, and it was just the sound of New Orleans. In some ways I heard the image. This is really dope and this is really timely. Someone on their path, doing their thing. I don’t know where they’re going, I don’t know where they’re coming from. I kind of love that it’s not discernible who this is. In that broad expanse of what life can be in New Orleans. I don’t think I could see enough of New Orleans. [That’s the music of New Orleans]. I felt the musicality of the people, the rhythm of New Orleans in that image. That’s not the commercial aspect, it’s just New Orleans.

CR: What does the phrase “A Gathering Together” mean to you, and what does it mean to you that this interview is taking place with A Gathering Together: A Literary Journal?

TM: Thank you to everyone at the team of A Gathering Together, for it existing. I appreciate you all reaching out and asking. I had followed the journal since its inception. It helps me take myself more seriously as an artist and an image-maker. It helps me [see] there are people who care about what I’m doing. I hope I’ve said something useful to some folks. If so let me know, if not let me know, we’re gathering together.

It implies so much about what we should be orienting ourselves to. Knowledge, wisdom, community are the things that come to me when I think about a gathering. You can’t gather by yourself. I see it as a nice play on the need to return to the technology of community. Little “c” community, not big “c” community. This endeavor doesn’t make a definitive statement on anything, and deals with you where you are. I feel like it is a rich and nutritious piece of content that really is the collective enlightened experience [in the words of a cat from Detroit I knew]. Community in practice, not just a community in name. It’s active, it’s activating. I almost read it as a gathering, together.

Tafari Melisizwe and Roy DeCarava are kindred artisans. Connected by many things, least of which being their appreciation of sports. Melisizwe played basketball in high school, and today still enjoys watching the occasional soccer match. DeCarava spent years working for Sports Illustrated, and is quoted as saying in the 1970s that “he wouldn’t want to work for anyone else right now.”

Two black men, two black artists, two black photographers. Separated in linear time by decades, but in craft by a distance far less daunting. In the shadows of their images, the connections between the two find refuge in a time that is phenomenological. Firm believers in the power of black-and-white photography, it is in the shades of gray in their photographs where their connection reaches across space and time… it is in the shades of gray where we see through their shared Black eyes.

When asked about his comfort on the other side of the lens, Melisizwe told me that “I don’t prefer being in front of the camera, I prefer being behind the camera. [But] as I’ve gotten older that’s changed because I think I’m a little more interested in seeing myself than I was before. For people that I love, in the future, to be able to see me.” Age seems to have imbued in Melisizwe an appreciation not only of his own seeing, but of being seen by others. In our conversation, he wanted to make sure that people know “I have a lot of fun doing what I do. I laugh a lot. I smile a lot.” There is no telling what the future holds for The Indigenous Lens, but I would venture to imagine that there will be more laughs, more smiles, and more of that poetics of being that Kevin Quashie has termed black aliveness.

It’s not every day you get to interview someone who attended the same high school as you, over a decade after each of you attended that high school. Shoutout to Baltimore always, and to Woodlawn High School especially. Thank you A Gathering Together for the opportunity.

[1] Kevin Quashie, Black Aliveness, or A Poetics of Being (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 66.

[2] Ray Gibson, “Roy DeCarava: Master Photographer,” Black Creation: A Quarterly Review of Black Arts and Letters 4, no. 1 (1972) in The Soul of A Nation Reader: Writings by and about Black American Artists, 1960-1980 ed. by Mark Godfrey and Allie Biswas (New York, NY: Gregory R. Miller & Co. 2021): 423-425.

[3] A.D. Coleman, “Roy DeCarava: Thru Black Eyes,” Popular Photography 66, no. 4 (April 1970) in The Soul of A Nation Reader: Writings by and about Black American Artists, 1960-1980 ed. by Mark Godfrey and Allie Biswas (New York, NY: Gregory R. Miller & Co. 2021): 195-201.

[4] https://www.humanitieskansas.org/get-involved/kansas-stories/the-big-idea/big-idea-seeing-the-world-through-the-eyes-of-gordon-parks

[5] Ray Gibson, “Roy DeCarava: Master Photographer,” Black Creation: A Quarterly Review of Black Arts and Letters 4, no. 1 (1972) in The Soul of A Nation Reader: Writings by and about Black American Artists, 1960-1980 ed. by Mark Godfrey and Allie Biswas (New York, NY Gregory R. Miller & Co. 2021): 423-425.

[6] Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom (Durham NC: UNC Books, 2011) 73.

[7] https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/primary-documents-african-american-history/1926-langston-hughes-the-negro-artist-and-the-racial-mountain/

[8] Ray Gibson, “Roy DeCarava: Master Photographer,” Black Creation: A Quarterly Review of Black Arts and Letters 4, no. 1 (1972) in The Soul of A Nation Reader: Writings by and about Black American Artists, 1960-1980 ed. by Mark Godfrey and Allie Biswas (New York, NY: Gregory R. Miller & Co. 2021) 423-425.

[9] A.D. Coleman, “Roy DeCarava: Thru Black Eyes,” Popular Photography 66, no. 4 (April 1970) in The Soul of A Nation Reader: Writings by and about Black American Artists, 1960-1980 ed. by Mark Godfrey and Allie Biswas (New York, NY: Gregory R. Miller & Co. 2021): 195-201.

[10]Dawoud Bey, “Reflections on Harlem U.S.A.” statement about exhibition held at the Studio Museum in Harlem, January 14 – March 11, 1979) in Matthew S. Witkovsky, ed., Dawoud Bey: Harlem, U.S.A. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012) in The Soul of A Nation Reader: Writings by and about Black American Artists, 1960-1980 ed. by Mark Godfrey and Allie Biswas (New York, NY: Gregory R. Miller & Co. 2021): 579-580.

[11] Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes, The Sweet Flypaper of Life (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1955): 62-64.